In November last year, I made my way to Dubai airport to catch the early African Express flight to Mogadishu. To my surprise, several other Somali-Australians who I knew at home in Sydney were already in line, waiting to board the same plane.

One woman had brought her two teenage sons with her. It would be their first visit home. I couldn’t help but chuckle as I recognised the fear and irritation etched on their young faces. I wore the exact same look seven years ago when I made my first trip to Mogadishu from Sydney. I lived in the city for a year, and was now returning for a short visit.

While waiting to board, I got into an argument with a random man who tried to trick me into checking in a mysterious box of ‘dates’ under my name to Mogadishu. I refused but he kept insisting. My friend yelled at him and he hurried off. I still wonder what exactly was in that box of alleged dates.

The group of women I was travelling with cheered as we stepped off the plane at Mogadishu International Airport. They did what homesick citizens would do: they posed for photos under the Somali flag. An airport official immediately began yelling at us to move on. It was the start of the first pointless argument out of a series of pointless arguments I had to witness in Somalia.

The sun was blistering hot on my skin and I was uncomfortable in my abaya. I never wore it back home, and it seemed ridiculous and restrictive in this heat. I awkwardly tried not to trip over it as I hurried into the arrival lounge. As I queued with the rest of the passengers, I was told I was in the wrong line. A weird feeling passed over me as I realised I was being directed to the foreigners’ queue. There is something humbling about arriving in your home country, the land of your birth, and having to wait in the foreign citizens’ line. Indeed, I was a foreigner who could not tell left from right in this city; a foreigner whisked away as a toddler only to return when it suited me. I left Somalia in the nineties during the outbreak of the civil war and emigrated to Australia with my parents and siblings.

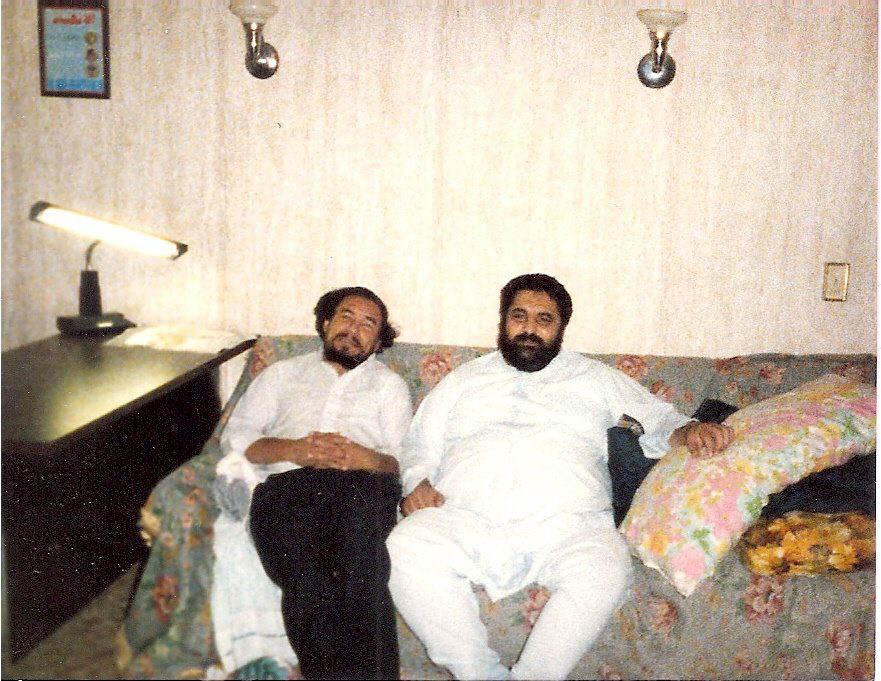

I paid US$ 50 for my foreigner visa, and stepped outside, right into the arms of my uncle and father. I wrestled myself away from the eager taxi drivers offering to provide a lift and followed my family out of the airport. I stopped abruptly as an envoy of African Union tanks passed by, followed by a truck full of Somali soldiers. The African Union troops are in the country to bring peace and order after a long and brutal civil war. This envoy would become a frequent sight during my stay. As I looked at them in bewilderment, one of the Somali soldiers cheekily winked at me. My uncle was quick to reprimand him. I smiled, shook my head and made my way towards our car where my grandfather was waiting for me. I was home.

We snaked our way through rush hour traffic as we drove from Mogadishu to Balcad, my family’s home town that’s an hour’s drive away. The drive gave me a chance to get reacquainted with the city. Some things were exactly as I had left them: the noise, the smells, the goats and donkeys stopping traffic, the war-torn buildings brimming with people. But there were also new sights: soldiers in uniform, a myriad of construction projects competing with each other, people counting money in public, the Turkish flag waving proudly from various buildings, teenagers texting away on their smartphones. There were school children in their brightly coloured uniforms walking in groups to catch the bus home; elderly men sitting under trees for shade, quietly sipping on tea; the constant yelling of bus drivers trying to hustle passengers into their vans.

Mogadishu is a noisy city. It has to be. Everything in the city happens while the sun is up. You get a sense of frantic energy but at the same time nobody is in any real rush. The people here subscribe to the philosophy “whatever happens, happens”.

I noticed that every woman and even young girls were now wearing either the burka or jalabeeb (head-to-toe burka). I left Somalia after a one-year stay in Mogadishu in 2005, before the Islamic Court and before al-Shabab. In that time – which honestly feels only like months to me – it seemed like the bodies and behaviour of Somali women changed. The traditional baati (long dresses) were replaced with head-to-toe jalabeebs. I stared at the women wearing them. In turn they stared at me.

As we made our way out of Mogadishu, we stopped at a government-run checkpoint. I was quite familiar with militia-run checkpoints from my last visit, so this was a welcome change. Then I remembered that I was carrying a large amount of US dollars on me. I froze. As I got out of the car, I fumbled and quickly hid the money in a hole inside my handbag. I had no idea if my money would be taken but I decided it was better to be safe than sorry. The Somali female soldier went straight for my handbag and then my wallet. I stared at her blankly as she examined them and tried not to smile. She let me go.

This checkpoint manned by Somali and Ugandan soldiers became a daily ritual for me as I shuttled between Balcad and Mogadishu. The men were searched in the open while the women were privately body-searched by female soldiers. I started a curious relationship with a Somali female soldier who nicknamed me Camerista. Whenever she saw me coming, she would yell, “Camerista! My friend!”

Halfway between Mogadishu and Balcad, a group of soldiers stopped our car to catch a lift. I was taken aback but not completely surprised at their nerve to barge their way into our car. One of the soldiers tried to chat to me but my uncle sternly put a stop to it. “Don’t concern yourself with girls that are not concerned with you, how about you do the job you are paid to do!” It doesn’t matter if you have a knife or an AK-47, my uncle will put you in your place.

I chuckled, closed my eyes and took a nap. When I woke up, I was in Balcad, the home of my father, his father, and his father’s father.

This is the first of a series of posts by Samira Farah about her recent visit to Somalia. She is a freelance writer and events organiser based in Sydney, Australia. Visit her blog at brazzavillecreative.com