Up a bumpy, winding dirt track in the mountains of northern Ethiopia, past two bulls chewing pasture and a rondavel built from sticks and cow dung, is the modest home of Lubaba Abdella, its mudbrick walls reinforced by eucalyptus bark and topped by a corrugated roof.

Abdella has lived a lifetime, yet she is still in her teens. She dropped out of school, married, divorced three months later and emigrated illegally so she could cook and clean for a family in Saudi Arabia, earning money to support her parents and eight siblings. Now she is home and back to square one.

Three-quarters of girls in the Ethiopian region of Amhara become child brides like Abdella, according to the London-based Overseas Development Institute. Many also join the so-called “maid trade”: up to 1 500 girls and women leave the east African country each day to become domestic workers in the Middle East. A study has shown for the first time how these pernicious trends feed off each other.

In Ethiopia’s Muslim communities it is often deeply shameful or “sinful” for girls to remain unmarried after they begin menstruating, notes the ODI. But once girls are married and sexually initiated, parents consider their social and religious obligations complete.

The thinktank’s researchers in Amhara found it was therefore becoming common for parents to insist on marriage followed by a swift divorce so that their daughter was free to migrate and send her earnings home to her parents, not her husband. The fact a girl had already been “deflowered” meant she was seen as less likely to be disgraced by foreign men. “It’s a question of virtue and virginity,” one local researcher said. “Better to lose it in a dignified way.”

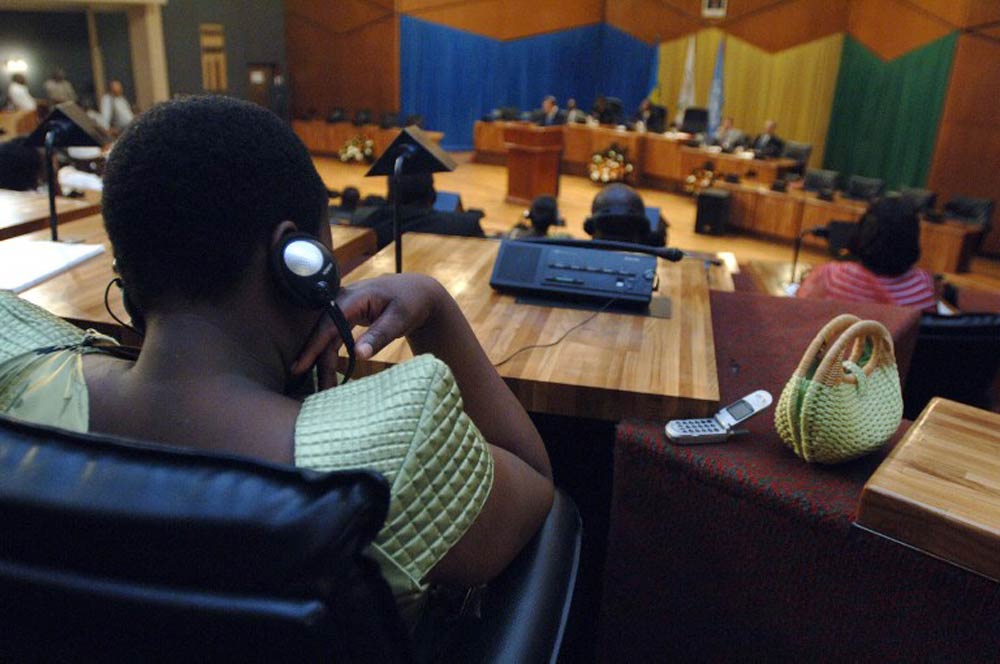

Girl Summit

The findings are being released ahead of the first Girl Summit, hosted by the British government and Unicef on Tuesday with the stated aim of ending female genital mutilation and child marriage within a generation. The ODI will warn that parents who see their daughters as commodities are pushing record numbers of girls into abusive early marriages. Some 39 000 child brides marry every day – 14 million a year – often against their will. Amhara has Ethiopia’s lowest average marriage age – 14.7 years – and one of its highest illiteracy rates.

Abdella, now 19, illustrates the constrained choices and warped pragmatism that many here face. She was 16 when she dropped out of school for an arranged marriage to a 22-year-old. It lasted only three months. “He used to hit her,” said Abdella’s mother, Zeyneba Seid. “They didn’t like each other so divorce was inevitable.”

It was hastened when Abdella’s husband wanted to seek work abroad. Speaking Amharic through an interpreter, she recalled: “If a man migrates alone to the Middle East, he will cheat on you. But it’s difficult to migrate with your husband and still support your family. That’s why I wanted a divorce.”

Nevertheless, Abdella believed even her short-lived marriage would be an advantage overseas. “I was told I’m young and it’s better if I know what marriage is before migrating. People in the Middle East might force us to sleep with them. If a girl has been married and goes to Saudi and is raped, it’s not as bad as for one who’s single. If she’s single and bears a child, it’s really difficult to come back here. But if she’s been married, it’s OK.”

The ODI found that some girls also choose to migrate, against their parents’ wishes, out of a sense of filial piety that tends to be weaker in boys. Abdella says it was her own decision because her family was in poverty, farming just one hectare of land. Notably she has an elder brother who is still at school. “He was asked to migrate but he wanted to continue his education, so I had to go and earn. I wanted my family to be better off.”

For the residents of Hara, a remote mountain village where the air fills with birdsong, cocks crowing and the Muslim call to prayer, and the streets with bajajs (motorised three-wheeled rickshaws), camels and boys herding goats, Saudi Arabia offers an alluring promise of riches just as America once did to Europe’s huddled masses. The results can be seen in a series of neat concrete houses with colourful paintwork, barred windows and a sprinkling of satellite dishes that have sprung up in the past five years, funded by wages from the east. Owning a corrugated roof is a status symbol here. For those still living in older houses made from mud and thatch there is the perpetual struggle of keeping up with the Joneses.

“Seeing the houses that were built makes you wish you’d migrated,” said Abdella, who sleeps with her family on the floor of two cramped rooms. “We have a lot of needs: clothes, shoes. Most of the time we cannot afford them, whereas people in Saudi had money.”

Working in Saudi Arabia

It is now illegal under Ethiopian law for anyone under 18 to migrate to work but Abdella, like thousands of others, got a passport by using a fake ID and lying to the authorities that she was 27. The entire process cost 15 000 birr (£445). She cooked, cleaned and washed clothes for a Saudi couple and their three children and was paid 800 riyals (£125) a month, paying off the debt and earning enough for her family to be connected to electricity and water and cover food bills.

The job came to an end after 20 months when Saudi Arabia carried out a mass deportation of illegal foreign workers. “I’m doing nothing at the moment,” sighed Abdella as two chickens scampered across the house’s dirt floor. “Seeing my family suffering here, I don’t want to remarry, I just want to support my family. I want to go back to the Middle East. There’s no other option because the wage is really low here.

“My younger sister, who’s 15, is planning to go. I advise her to because she can earn more and do whatever she wants. But she would have to marry first – it’s our custom.”

The pattern of marriage and divorce is becoming increasingly common. Aesha Mohammed (16) recently married a man six years her senior, only to divorce after two months because she refused to quit school. Her elder sister also married and divorced, then migrated to work in Saudi Arabia. Mohammed, who wants to become a doctor, said: “Sometimes when I joke with her, ‘I want to drop out of school and come to Saudi’, she says no, stay in school because it’s hard there. There is a lot of work and it’s a burden.”

The journey to get there can also be treacherous. For some it involves more than a week on foot to Djibouti, then a six-hour boat ride to Yemen after dark, followed by 15 to 20 days travelling by road to Saudi Arabia. Habtam Yiman (24) who married aged 12 and has married twice since, said she was detained in Yemen because officials did not believe she had a sponsor. “They check your blood type and take some of it for the hospital,” she said. “I saw a man whose blood was completely drained out of him and he was left to die.”

Yet still thousands are pouring in for the sake of their families. The ODI, which hosted a field visit by the Guardian last week, reports that some girls go because they “feel inferiority” and have been “seduced by the glamorous stories” told by illegal brokers. The fate that awaits them can include overwork, non-payment, social isolation and abuse.

When Zemzem Damene set off to work in Kuwait, she was a normal girl who wanted to earn money and be like her friends. Today she is confused, withdrawn and virtually mute, a stranger to her own family. Something happened to Damene in Kuwait and no one knows exactly what.

As the 20-year-old peered nervously from under her veil and picked at her hand, her mother, Engocha Sete, recalled: “She wanted to go and I couldn’t stop her. She said her friends went to the Middle East and brought home shiny objects. She wanted that and she had to have what she wished for.”

Her father, Damene Alemu, added: “I was sad she wanted to go. I asked her to marry here but she said, ‘You don’t have a lot of money to marry me off, it’s not logical.’ Marriage is an expensive thing for the father, with buying clothes, organising a party, paying two months of utilities. She said it’s best that she go off to the Middle East.”

But the plan backfired and Damene actually lost more money than she made, forcing the family to sell cattle. According to Alemu, his daughter’s first employer took all the money she had and even the clothes she brought from home, and that was the start of her decline. “She went to a hospital in Addis Ababa but they didn’t tell us what the problem was, only that it’s a mental illness.”

Damene’s mother added pensively: “She doesn’t do anything now. She doesn’t speak much. Most of the time she sleeps. Now she’s sick, there’s nobody wants to marry her. If she gets better, we’d like her to get married. But because she’s lost so much, the only thing she talks about is money.”