A “detoother” or a “dentist” is a gold-digger looking for a wealthy partner, while “spewing out buffalos” means you can’t speak proper English. And a “side-dish” isn’t served by a waiter.

Those and other terms are articles in Uganda’s strange, often funny locally-adapted English known as “Uglish,” which is now published for the first time in dictionary form.

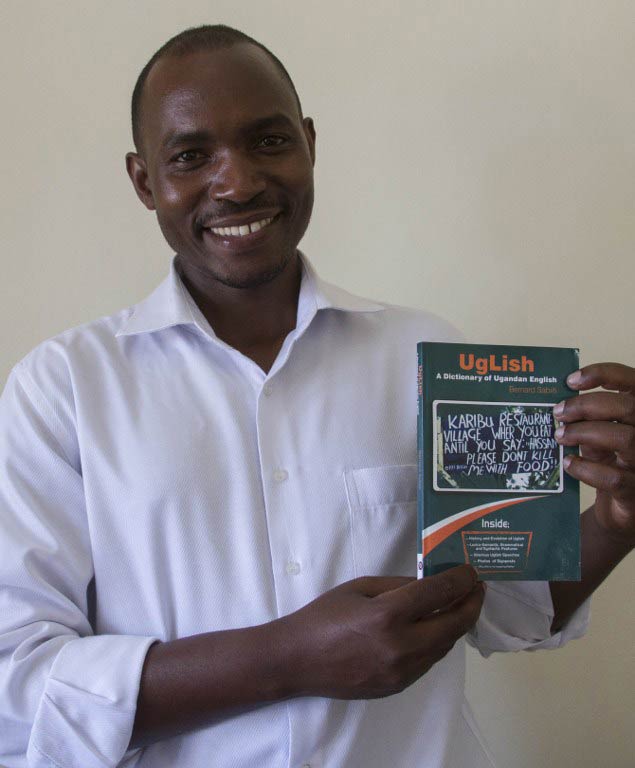

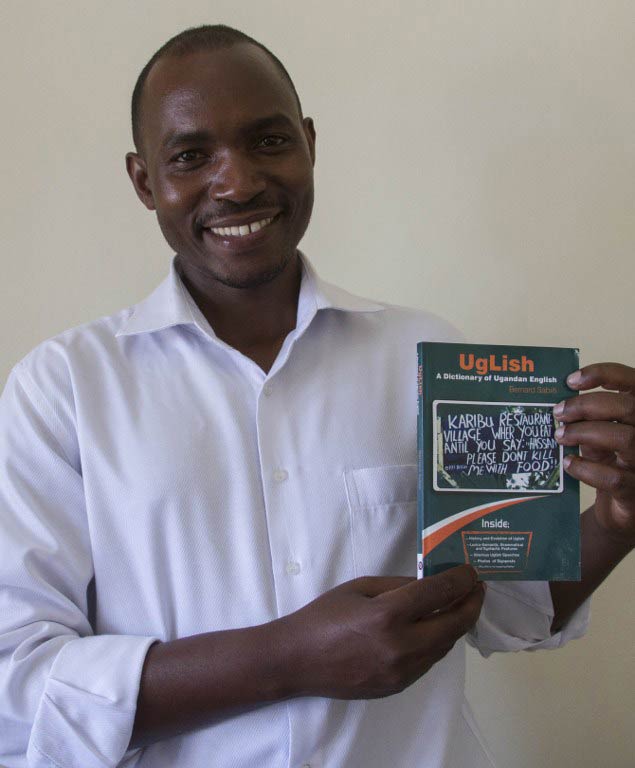

“It is so entrenched right now that, even when you think you cannot use it, you actually find yourself speaking Uglish,” Bernard Sabiiti, the author of the first Uglish dictionary, told AFP.

“Even as I was researching, I was surprised that these words are not English because they were the only ones I knew. A word like a ‘campuser’ – a university student – I used to think was an English word.”

Uglish: A Dictionary of Ugandan English, which went on sale in bookshops across the east African country late last year, contains hundreds of popular Uglish terms, some coined by Ugandans as far back as the colonial period.

Sabiiti (32) said the informal patois was greatly influenced by the local Luganda language, and is a “symptom of a serious problem with our education system” that he claims has been deteriorating since the 1990s.

Uglish is largely dependent on sentences being literally translated, word for word, from local dialects with little regard for context, while vocabulary used is derived from standard English.

Meantime, Sabiiti says, influence from the Internet, local media and musicians have seen additional words and phrases created and slowly enter the lexicon.

The result is colourful but at times confounding expressions. If you haven’t seen someone for a while, for example, you’re “lost”, while if you “design well”, you are snappy dresser.

Today, Uglish is used by people from all walks of life, but particularly popular with youths.

English is the working language in Uganda, and it remains the only medium of instruction in schools and in official business.

But Sabiiti said everyone from the president to simple farmers speak at least some Uglish, which varies according to region, tribe and gender, and is regularly seen on signposts.

“MPs are almost notorious at using Uglish, you see it in parliamentary debates,” said Sabiiti.

Live-sex and side-dishes

But it wasn’t until 2011, a year after the term Uglish – pronounced “You-glish” – had been coined on social media, that Sabiiti began keeping newspaper cuttings, conducting interviews and searching online for material for his book.

“I knew that people talked a lot about this, and my friends used to laugh about it,” said the author, whose fulltime job with a think tank has taken him to different regions of Uganda, and exposed him to the different types of Uglish.

His book contains a brief history of Uglish, and a glossary of terms relating to education, telecommunications, society and lifestyle, food, transport, sex and relationships.

One phrase commonly used when discussing the latter is “live sex,” which means unprotected sex – a term thought to have derived from the live European football games Ugandans love to watch.

“When the ministry of health is doing campaigns to warn young people against unprotected sex, they use ‘live sex’, because everybody will understand it,” said Sabiiti.

On the same subject, if you’re a “side-dish”, you are someone’s mistress.

Sabiiti’s book has proven popular among the middle class, including academics, and with locals and foreigners alike. To date he’s sold about a thousand copies.

“I’ve had incredible feedback from professional linguists, ordinary readers – some even suggesting more phrases – so I’ll be doing another edition,” said Sabiiti.

“I don’t see it disappearing. I’m looking forward to seeing five years from now how many new words and phrases have joined the lexicon,” he said, adding some teachers, particularly in state schools, are passing Uglish on to their students.

But, as the author stresses in the final chapter of his book, there comes a point when Uglish stops being funny.

In 1997 Uganda introduced universal primary school education, which eliminated official school fees and made education accessible to millions more children.

But literacy rates remain low: more than a quarter of the population cannot read or write, according to the UN, and critics say standards remain low in many schools.

“Uglish is not something that should be encouraged, particularly for young, impressionable children. They really should learn what they call proper standard English.”