It’s hard to know where to look in the crowded interior of the Murenju general store. The entrance is flanked by multicoloured mattresses stacked like surreal sandwiches. Rolls of linoleum flooring stand under shelves groaning with speakers, while cooking pots hang from the rafters amid the bunting of adverts for a pay-TV service.

Sally Kayoni, the shopkeeper, stands on tiptoe to be seen over a counter lined with car batteries, radios and DVD players. Yet the prime retail space on the eye-level shelf behind her is given over to small solar lamps presented in a neat row. They get pride of place because they are among her bestsellers.

“I had so many customers asking for them,” she says. Each month she sells more than 200 of the simple devices, which cost a little over £6 and when charged in direct sunlight will light a small room from dusk to dawn.

The 34-year-old runs one of the busiest shops in Bomet, a fast-growing town of four streets and clanking construction two hours’ drive from Kenya’s world-famous safari destination, the Masai Mara. With its paved roads and electricity, it is typical of east Africa’s new boom towns, servicing a hinterland of small farms that operate off the grid, accessible by dirt roads plied by motorcycle taxis.

Kayoni first started to notice the solar lamps when they were brought to the area in 2012 in a striking canary-yellow van owned by SunnyMoney, a subsidiary of the UK-based charity SolarAid.

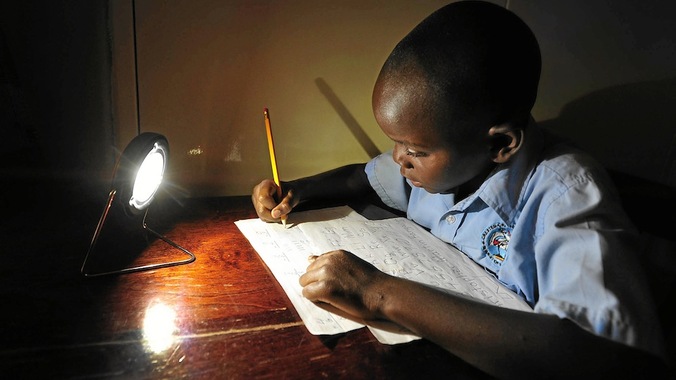

They were initially distributed through the area’s schools, where head-teachers were persuaded to pitch the lamps to parents as a way of helping children to do their homework. One year on, a conventional market for the lights has been created and they are sold in shops.

A business owned by a charity may sound novel, but rather than giving away solar lamps, SunnyMoney has deliberately chosen a commercial strategy, in the belief that this way its simple but effective technology can find an enduring foothold.

“We take a business approach because that is what this market needs,” says Steve Andrews, chief executive of the not-for-profit company. He wants to see solar technology follow in the footsteps of mobile phones, which have become ubiquitous in Africa over the past decade, thanks to a support network of retailers and services.

SunnyMoney has sold close to one million lights, making it the biggest retailer of solar lamps in sub-Saharan Africa. On average it makes a loss of 13p on each light it sells, but when the goal is to open up new markets by selling as many as possible – rather than make an immediate return – that is a sign of success.

“Philanthropy allowed us to be aggressive and pursue markets that didn’t exist before,” says Andrews, “because we don’t have to answer to shareholders seeking an immediate return.”

Some 40 000 lights have been sold in the Bomet area alone and SunnyMoney is on course to break even in the next two years, at which point profits will be ploughed back into the parent charity SolarAid. What some donors might find controversial is the chief executive’s belief that people value more a product they have to pay for than something given away.

Access to electricity

Much of sub-Sahara Africa is littered with the detritus of good intentions – projects from refrigerated fish-packing factories on desert lakes, to secondhand computers – that failed to meet real needs in the communities where they landed.

Fewer than 20% of Kenyan homes have access to electricity and are therefore forced to use fossil fuels such as kerosene for lighting. Households that give up the kerosene lamps they used previously can expect to make a saving of roughly £40 a month, which can be spent on school fees, food and other goods. “Previously the money was leaving the community and going to global oil companies [through kerosene sales],” Andrews says. “Now it is going to local businesses.”

The educational impact of thousands of solar lights in once-dark homes can be measured around Bomet. Christopher Sigei, the area education officer, has been doing just that: “In the evening it has been working small miracles.”

Asked about local access to electricity, he smiles and describes it as “zero point something”. The average mark in national exams in the poorest neighbourhood, he points out, has risen from 215 to 233 in the first year since the lights went on sale.

These kinds of benefits have turned headteachers such as Stanley Rugut into solar evangelists. The beaming 58-year-old, who has sold about 6 000 lamps, drives around the area’s rutted roads in a battered old estate car with leopard-skin seat covers and a solar panel on the dashboard. “I like to charge the lights while I’m driving,” he explains.

He talks about old model S1 and S2, as well as newcomer light system Sun King, with the same enthusiasm with which smartphone owners debate the pros and cons of new brands and handsets. Rugut has been rewarded for his hard work with lights rather than cash, and his skills as a salesman have allowed him to amass dozens of the lamps.

“I have all of them, and people are always coming round and very excited to see them,” he says.

Meanwhile, back at the Murenju general store, the one thing you will not find is kerosene. “I no longer sell it,” says Kayoni. “After I started selling these,” she points at the solar lamps, “there was no one asking for it any more.”

Daniel Howden for the Guardian