Seven years ago, Dagmawi Yimer was “between life and death” when Italian navy officers rescued him and 30 others from a skiff in heavy seas between Libya and the island of Lampedusa.

Today, Yimer directs documentary films about immigrants like himself from the home he shares with his Italian partner and their two-year-old daughter in the northern city of Verona.

He is part of the fast-growing immigrant population that is changing the face of Italy, just as it has transformed the populations of more northern European countries such as Britain, France or Germany.

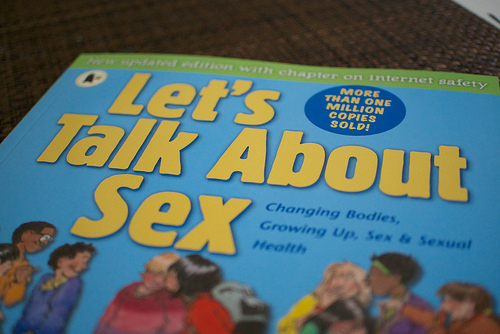

He is also one of many foreigners who are trying – through cultural initiatives such as films and books – to change the racist views of many Italians of the immigrants in their midst.

Contrary to popular perceptions, immigrants are making their mark across the Italian economy, politics and society. African-born author Kossi Komla-Ebri, a 59-year-old medical doctor, has published six books, all in Italian.

“Many immigrants think our emancipation is only economic and political, but we are convinced it’s cultural and that we can have a more profound influence through culture,” he said.

It isn’t easy. Italy’s immigration wave is swelling just as the country is struggling to emerge from its deepest economic downturn in the post-war era.

Nearly eight percent of the population here is foreign born, and in 50 years the number will triple to 23%, according to a projection by Catholic charity Caritas.

To help pay the pensions of an ageing population and to ensure long-term growth, Italy needs to integrate its immigrant population into the workforce, economists say.

Anti-immigrant sentiment

But high unemployment, especially among non-student young people, has fuelled anti-immigrant sentiment among the Italian mostly-white population.

Italy’s one-million strong Afro-Italian community, a fifth all legal immigrants, got a high-profile representative last April when African-born Cecile Kyenge became the country’s first black minister.

It did not take long before she was likened to an orangutan by a well-known politician and had bananas thrown at her at a public meeting.

Politics

Many white Italians view the Afro-Italian community and other immigrants as cheap labour or petty criminals – partly because many work as domestic help and farm labourers or sell counterfeit goods in the streets of big cities.

Moreover, children born to immigrants do not automatically receive citizenship even if they are born on Italian soil, attend Italian schools and spend their whole lives in Italy. They must wait until they turn 18 to apply.

Though Italy was a colonial power in Africa in the 19th and 20th centuries and migrants have come to Italy for decades, the country has mainly served as a transit route for the rest of Europe and so remains an overwhelmingly white country.

Over the past two decades, another factor has thwarted attempts to develop a comprehensive and inclusive immigration policy: the anti-immigration Northern League, once a key ally of Silvio Berlusconi’s former coalition governments.

Backed up by TV images of overcrowded boats being rescued off Italian shores, Northern League politicians portray migrants as invaders coming to steal jobs – rhetoric that neglects Italy’s history as a country of immigrants to North and South America in the 19th and 20th centuries.

It was high-ranking Northern League member Roberto Calderoli who likened to Kyenge to an orangutan last year.

Members of the neo-fascist Forza Nuova, or New Force, party were suspected by police of throwing bananas at her during a public round table on immigration. It denied responsibility.

The party also left mannequins covered in fake blood outside a Rome administrative office, urging her to resign because “immigration is the genocide of peoples”.

Kyenge seems to have taken it all in her stride, never losing her calm in public and sticking with her goal of making it easier for immigrants’ children to gain citizenship.

Only last month did the 49-year-old she reveal that she too had been a “badante”, or house servant, for six years to pay her way through university, saying it had been one of the most difficult times in her life.

Born in the Democratic Republic of Congo to a tribal chief with 38 children and four wives, she ended up an eye surgeon until she became a lawmaker and minister earlier this year.

“I’m not coloured, I’m black,” she told Reuters in an interview in her office in central Rome, rejecting the phrase “di colore” or “coloured”, which many think is the politically correct Italian term for blacks.

“It’s the proper term because it forces everyone to face the reality of a multi-ethnic Italy.”

‘Boiled elephant knees’

Italy’s immigration policies are ill-equipped to deal with the thousands of immigrants who show up – with scant identification and on rickety boats – on its southern shores.

Rules dating to 2009 and Berlusconi’s then conservative government make entering without proper documentation a crime, requiring officials to report clandestine migrants.

As a result, those who survive often treacherous journeys – at least 366 Ethiopian migrants drowned while crossing to Italy in October – often linger for months in makeshift immigration centres and then disappear withinItaly or eleswhere in Europe.

During the first 11 months of this year, 40,244 illegal migrants reached Italy by boat, almost four times as many as a year earlier, according to Save the Children.

The number living in Italy is not known with any precision, but the OECD has estimated that, alongside the 5-million legal immigrants, there could be as many as 750 000 illegal ones.

One of the community’s oldest cultural initiatives is the “African October” festival inaugurated 11 years ago in the northern city of Parma and now celebrated in Rome and Milan, showcasing African artists, writers, musicians and filmmakers.

“The meeting between Africa and Italy is very important,” says festival founder Cleophas Adrien Dioma, who was born in Burkina Faso. “Culture is born out of such encounters.”

Komla-Ebri, who came to Italy in 1974, is a doctor in a hospital north of Milan and writes in his free time. This year his book Imbarazzismi – an Italian neologism merging the words “embarrassed” and “racism” – was printed by Edizioni SUI, a publisher owned by an Eritrean-born Italian.

In the book, Komla-Ebri writes about when his white Italian wife took a walk in the park and a stranger complimented her for adopting two “African orphans”, or the time her friends ask her what he eats, “no doubt with the chilling thought of a menu of smoked snake or boiled elephant knees”.

“My irony is a defence mechanism,” he said.

The anecdotes capture the often naive quality of racism in Italy, infamously exemplified by Berlusconi’s 2008 remark – made in jest, he said – that the newly elected Barack Obama, was “young, handsome and suntanned”.

Yimer (36) harvested grapes in the south and later handed out fliers to university students in Rome until he took a video production class offered to immigrants by a non-profit group.

His fifth documentary film – released this month – is about three Senagalese men recovering from racist attacks.

Entitled Va Pensiero, after the chorus of an opera by Giuseppe Verdi about an immigrant’s nostalgia for home, the film follows the men as they try to come to terms with the hate and violence they endured.

The first man was stabbed and left for dead by a skinhead at a bus stop in Milan. Passersby ignored him for more than an hour. The other two were randomly shot by a radical right-wing thug who hunted down and murdered two other Senagalese men on the streets of Florence in 2011, and then committed suicide.

At an early screening of the film for possible distributors, the reaction was that of having been “punched in the gut”, according to one representative of the state-owned TV network, who suggested softening the tone.

Yimer and his Italian partners on the film, who have founded an association to collect the testimony of immigrants called the “Archive of Migrant Memories”, stood their ground.

“I’ve experienced a lot of prejudice,” he said, “and I see a worrying trend in Italy where racism is becoming more ideological.”

Steve Scherer for Reuters