The art of hair braiding has taken centre stage in pop culture in the past few months, from Chris Pratt’s surprisingly good French braiding skills to the return of the braid in Valentino to Vivienne Westwood Fall runway shows. In South Africa, a documentary by blogger Miss Milli B has served as a platform to discuss the politics of black hair in its various styles and textures. Most recently, Hollywood’s new darling Lupita Nyong’o highlighted hair braiding as a cultural practice in a video for Vogue.

Shot in a salon in New York, we see Lupita showing off her braiding skills on her friends’ hair. She learnt the technique from her aunt when she moved to the United States. She’s been doing their hair for years, and the camaraderie between them is evident.

Among Lupita’s group of friends is Nontsikelelo Mutiti, a visual artist whose recent exhibition Ruka (Shona for to braid/to knit/to weave) examines the social function hair braiding has apart from the aesthetic.

Mutiti is a Zimbabwean-born artist and educator who works across disciplines – fine art, design and social practice. Her Ruka project was exhibited at Recess, a non-profit art space in Soho, New York from June 3rd to August 2nd . It included an installation and an exhibition of hair braiding across traditional and contemporary contexts.

I caught up with her recently to discuss the project.

What was the source and inspiration for Ruka?

I accompanied my cousin to get her hair done one Sunday afternoon in 2010. We went uptown to Harlem, New York. Upon arriving at the braiding salon I was struck at how much it reminded me of hairdressing spaces back home in Harare.

The bright walls, loaded conversations, hair dressing posters, the vendors coming in and out selling small items like socks, candy and makeup. It was fascinating for me to realise the way the women working in the space had created a facsimile of something ubiquitous at home. The women working in the salon were not from Zimbabwe; they were form different parts of West Africa.

Future visits to Harlem revealed the multitude of women that do this work in New York City. They line 125th Street, soliciting business from potential clients from street corners to the doorways of multi-story buildings shouting out: “Braiding? Braiding, Miss? I give you good price!”

What has been the reception to your work so far in the States, particularly in light of actresses like Lupita Nyong’o promoting the tradition of hair braiding in popular culture?

I was glad that Lupita chose to highlight this cultural practice through a platform like Vogue. Giving visibility to the craft and taking ownership of this skill is a powerful statement that assigns value to braiding and braided hairstyles. There was a wonderful sense of community on set. On and off camera we shared personal experiences, advice and memories. It was wonderful to get my hair braided by Lupita. She is very good and I know how long it takes to build up these skills.

Braiding is not just about beauty; it is also about perseverance, trust and creativity. It is also such a generous act, spending time with someone, working on them. I hope the audience learnt all these things from the video. These ideas were certainly reinforced for me.

What has been the biggest lessons you’ve learnt in the process of connecting with a theme so pertinent to black female identity?

When we speak of black female identity we have two important themes pressing up against each other – gender and race.

Braiding is a means of adorning the body. Because of my socialisation I tend to imagine it as something associated with women, but looking at a range of cultures we find that people that identify as masculine also wear their hair braided.

Whilst discussing braiding and gender during a studio visit, Andrew Dosumno (an acclaimed Nigerian film director), mentioned that there are tribes in Nigeria where men who are involved in certain spiritual practices can wear braids.

It has been interesting to do this project at a time when people that identify as black in America are going ‘natural’. Braiding has become a very important grooming choice. There is something that feels akin to the ‘Black is Beautiful’ movement. People are choosing to sign their bodies with an aesthetic that refers to or acknowledges African heritage.

My observations have led me to consider how we read images of each other and what it means to emulate or aspire to a particular aesthetic. We are really using hair to mark our bodies and sign specific messages to each other: ‘I am proud of my ancestry’, ‘I will not be defined by western ideals of beauty’, ‘I am cosmopolitan’, ‘I am sophisticated’, ‘I have a range and breadth that goes beyond my traditional culture’. In the context of my home, Zimbabwe, we use braiding most often to add in new hair colour, texture and artificial length.

What has the audience reception been to your exhibition?

People coming into the space have really felt like collaborators more than an audience. The project emphasises community engagement and artistic research.

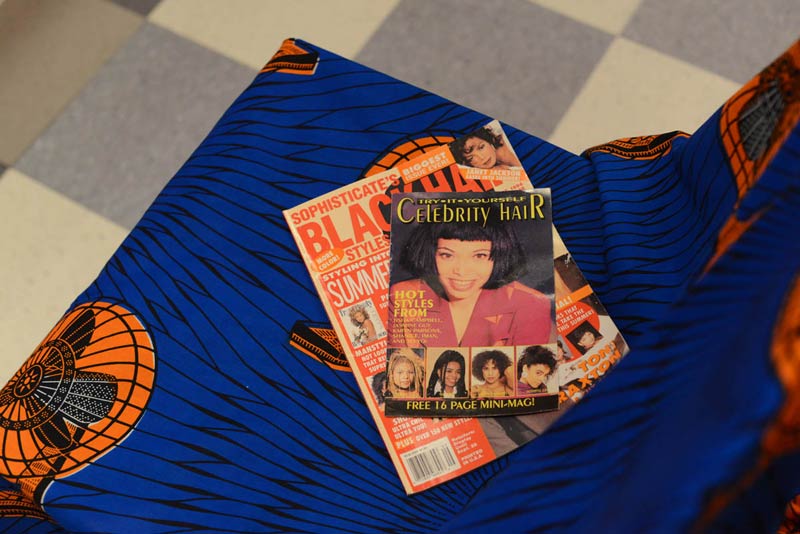

People have signed up for braiding workshops led by an invited facilitator. We have all felt empowered by the skills we have learnt. There are some of my older works as well as new sketches and collections of objects like combs, movies, fabrics and books, Nollywood and American movies in the space. The different elements that make up the installation have become wonderful tools for starting extremely meaningful, open conversations. Visitors have been very generous, sharing personal narrative or memories sparked by an object or image in the space.

Some people come in and are confused because they think it is a real hair salon. The project is playing with the boundaries between a few things. It is a salon and classroom and art studio, film screening room all at once. In essence that is what an African hair braiding salon is.

Will the exhibition be travelling to parts of Africa? How much more or less do you think it will it resonate with the audience here?

Doing this work in different communities is very important to me because I am not just making artwork; I am learning and sometimes teaching and sharing. I am sure the project will look and feel different depending on each iteration.The community have a big role in shaping what I make and get out of the experience. Because braiding has different connotations in different communities I am sure the work will read differently in different spaces. A range of interpretations makes for an even richer body of source material for continued research and art.

Have you found inspiration for your next exhibition?

The braiding project is ongoing. I am looking forward to starting a related publishing project and continuing to make new artworks based on different braiding patterns. I am also thinking of creating a dedicated space for continued practice and research around this craft.

I am developing a new series of video works titled Black Hair Aesthetic Study with my collaborator Shani Peters.

Jeanine Meyer, a colleague from Purchase College, is assisting me with coding online tools to teach a wider engage a wider audience in thinking and learning about the practice and cultural significance of braiding.

One project I am looking forward to is inspired by Dutch wax fabrics, another is about names.

My goal is to make work that can live in the world. It is wonderful to have institutional support for this type of work because it is not easy to fit all projects within a traditional gallery or museum setting. I look forward to other opportunities to share my work with people in formal and informal settings.