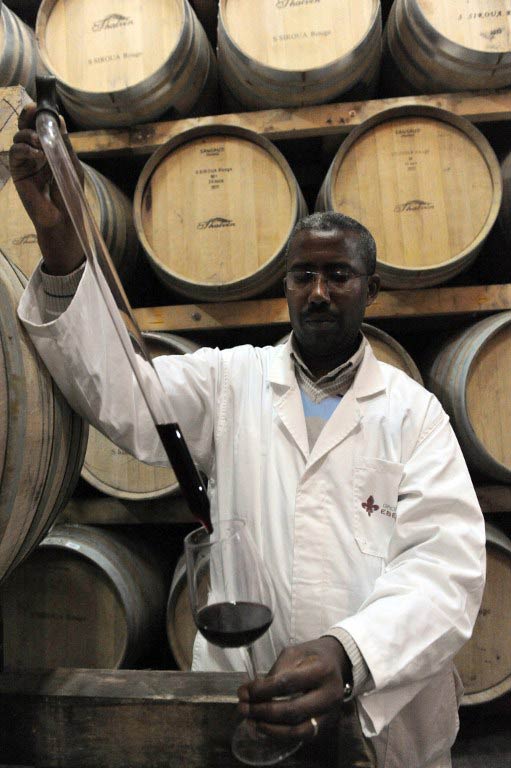

In a back alley in the Moroccan capital, the small household repair shop opened by Moctar Toure since escaping conflict in his native Côte d’Ivoire is doing a brisk business.

At the gates of Europe, Morocco has long been a transit point for migrants from sub-Saharan Africa looking to make the dangerous journey across the Mediterranean.

But tighter immigration controls and economic malaise in Europe have made the kingdom a destination in its own right for many.

In spite of the challenges that living in Morocco poses for migrants, Toure wants to stay permanently and got his legal papers last year.

“In the beginning it wasn’t difficult… it was impossible,” said the Ivorian, who migrated to Morocco nine years ago.

For several years after his arrival he relied on whatever odd jobs came up.

Toure struggled with a family to support, and it was only when he received his residency permit that he was able to secure a regular income.

With the help of local refugee agency Amapp, he got a roof over his head and rented a small space where he started his shop a few months ago in a working-class neighbourhood of Rabat.

Toure has even managed to employ a fellow Ivorian to meet demand from customers, most of whom are locals.

Although he is still working to integrate with society, “to return to Côte d’Ivoire would be something abnormal”, he said.

Multiple rejections

The alternative to staying in Morocco for many is a perilous sea voyage across the Mediterranean.

According to figures from the UN’s refugee agency, more than 2 500 people have drowned or been reported lost at sea this year trying to cross the sea to Europe.

They include people who have fled poverty-stricken nations in sub-Saharan Africa, preferring to risk their lives at the hands of people smugglers.

Those who remain in Morocco face a struggle to access education and healthcare.

This year, in response to a migrant influx and criticism from rights groups, authorities launched a scheme to naturalise migrants and refugees, who number about 30 000.

By the end of October, 4 385 residency permits had been delivered out of more than 20 000 requested.

Serge Gnako, president of the migrant organisation Fased in the economic hub Casablanca, arrived five years ago.

The 35-year-old Ivorian said he was deported several times and it was “difficult to access healthcare or to school your children”.

Gnako believes Morocco is changing, however, and is hopeful his one-month-old son will receive a solid education.

“I see our future in Morocco, and I hope my child will learn Arabic,” said the former university lecturer, who now teaches French.

Thanks to a recent ministerial ruling, Gnako’s local school in the residential suburb of Oulfa now has 15 students from sub-Saharan Africa.

‘No magic wand’

Migrants in Morocco still face problems after gaining residency, especially in finding work in a country where youth unemployment is near 30 percent.

“Your residency permit lets you look for work, not to find it,” said Reuben Yenoh Odoi, a member of the Council of sub-Saharan Migrants in Morocco.

Many still consider “going to sea”, said Odoi, a Ghanian, referring to the treacherous maritime crossing to Spain.

Several hundred migrants recently tried to storm the Spanish enclave of Ceuta on the north African coast, leading to the arrest of more than 200.

Driss el Yazami, president of the National Human Rights Council, the group tasked with Morocco’s residency programme, recognises that the process is still in its infancy.

“Getting your papers is not a magic wand for integration,” he said.

In addition, tensions between local and migrant communities remain fraught.

In August, a Senegalese man was killed in clashes between migrants and residents in the northern port city of Tangiers.

But such impediments do not faze Simon Ibukun, a Nigerian musician who plans to settle in Casablanca.

“I’m Moroccan, and I’m working hard to get into the management business and become my own boss,” he said.

Zakaria Choukrallah for AFP