German blacksmith Manfred Zbrzezny and his apprentices hammer, file and weld in a steamy, dark workshop on the outskirts of the Liberian capital Monrovia, surrounded by parts for AK-47s, bazookas and other deadly arms.

In another lifetime, these weapons were the cause of untold misery in a nation scarred by ruinous back-to-back civil wars, but now they are being transformed into symbols of hope for Liberians.

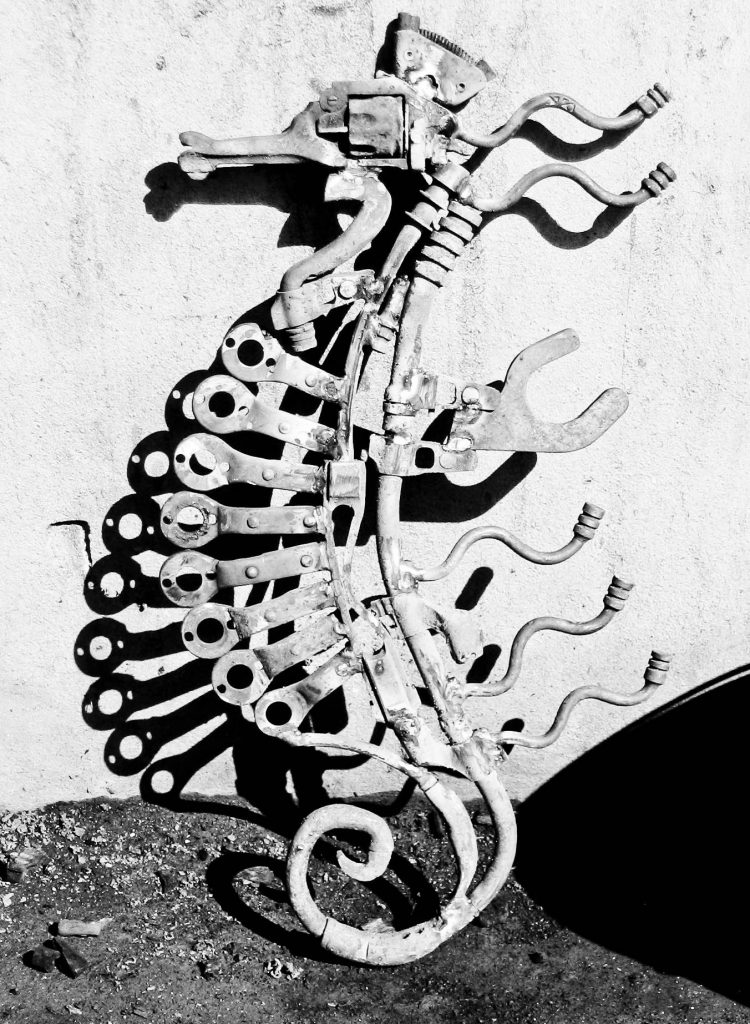

Since 2007, Zbrzezny and his team at Fyrkuna Metalworks have been gathering parts of weapons decommissioned during the disarmament process after the conflict ended ten years ago to turn them into ornate flowerpots, lamps, furniture and sculptures.

“It was strange from the beginning to work with weapons or instruments of destruction and suffering. The first two years I was working on this it remained very strange to me,” Zbrzezny said.

“When I had a piece in my hands I would think about what was happening now to the perpetrators who used these weapons, and what was happening to the victims, and I would put the piece down to go drink a cup of coffee because it was a little bit oppressive.”

Today, as he holds each weapon part, Zbrzezny is able to focus on its potential for bringing healing to the people of Liberia.

“I do some thinking on how to transform it into something different, how to transform something that was destructive into something constructive, how to transform something negative into something positive,” he said.

Deep psychological and physical wounds remain in Liberia after two civil wars which ran from 1989 to 2003, leaving a quarter of a million people dead.

Numerous rebel factions raped, maimed and killed, some making use of drugged-up child soldiers, and deep ethnic rivalries and bitterness remain across the west African nation of four million people.

Zbrzezny, who had worked as a blacksmith in Italy and Germany, came to Liberia in 2005, two years after the end of the rebel siege of Monrovia that brought a fragile peace to the west African nation.

He failed initially to make money out of his trade until in 2007 he was approached by the owners of a riverside restaurant who asked if he could put his skills to transforming the parts of old weapons into a marine-themed banister.

The project was such a success that he began making other pieces for the restaurant with parts from rocket-propelled grenade launchers and sub-machinegun barrels — then still commonplace in Monrovia.

He began collecting weapons parts from a German charity involved in Liberia’s disarmament process and made a business out of transforming instruments of war into candle stands, bookends, bells and bottle openers.

“So it was by chance that I got into this. Now I employ five young Liberians who are learning the trade at the same time,” said Zbrzezny, who calls his work “Arms into Art”.

One of Zbrzezny’s most ambitious projects was a “peace tree” fashioned in 2011 from weapons parts on Providence Island, an iconic part of Monrovia where freed slaves from the United States landed in the 19th century to found the new republic.

Momodu Paasawee, the caretaker for the area where the tree is exhibited, said it had become a symbol for reconciliation in post-war Liberia.

“Seeing this tree reminds Liberians that the war has ended and never should we return to war… Tourists and Liberian students come here to see the tree,” he said.

“Sometimes people come here believing that this is a real tree but I have to tell them that this is a peace tree made out of the barrels of guns.”

Zbrzezny, who is married to a Liberian woman who is expecting their second child, says most of his customers are expats, with few Liberians buying his wares.

Keen to expand his work, Zbrzezny has been trying to convince the United Nations mission in Liberia to donate its weapons scrap.

Leaving the past behind

A Truth and Reconciliation Commission was set up by President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf to probe war crimes and rights abuses between 1979 and 2003, and particularly during the brutal conflicts that raged in 1989-96 and 1999-2003.

The commission said a war crimes court should be set up to prosecute eight ex-warlords for alleged crimes against humanity but the government is yet to implement the recommendations.

A decade after the war, no money has been made available and the only Liberian to face trial is Charles Taylor, and that was for his role in neighbouring Sierra Leone’s civil conflict, not that in his own country.

The former leader is appealing a 50-year prison sentence handed down in May last year for supporting rebels in Sierra Leone in exchange for “blood diamonds” during a civil war that claimed 120,000 lives between 1991 and 2001.

Meanwhile a generation of traumatised children who witnessed untold horrors in Liberia are now struggling to come to terms with their country’s violent past as adults.

Emmanuel Freeman (28), one of Zbrzezny’s apprentices, was a child during most of the conflict and saw both of his parents slain.

“They were killed by guns. These are the same guns I am transforming today into something else,” he said. “I am excited, happy and very pleased to do that.”

But “sometimes when I am holding the scraps it reminds me what I saw during the war”, he added.

Zoom Dosso for AFP