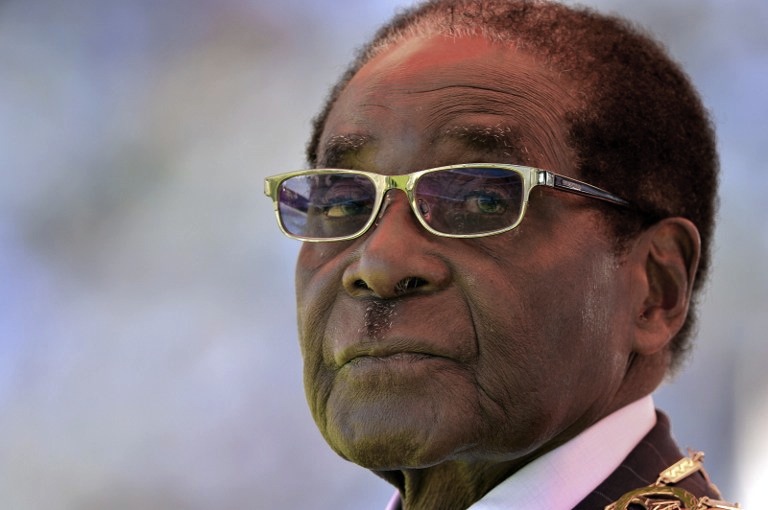

Africa’s leaders have appointed Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe to the largely ceremonial role of chairman of the 54-state African Union.

Mugabe, who has ruled Zimbabwe since 1980, is still respected by many for leading his country to independence from Britain. But critics believe the ‘president for life’ is out of touch with the people the African Union claims to represent.

Age is not a factor is the selection process for position for chairman of the Africa Union, but Africa is the world’s youngest continent, and at 90 years-old, Mugabe is among the estimated 5% of Africans who manage to live past their sixtieth birthday. In 2012, 85% of the population was under the age of 45, and life expectancy across the continent was 58 years.

Guess who’s the new African Union chairman? pic.twitter.com/2gbqTXVl5b

— B A B U S I (@designartistic) January 30, 2015

Wealth Mugabe’s government has been widely blamed for mismanaging Zimbabwe’s economy, plunging the country into desperate times. Though the extent of his personal wealth is not known, his penchant for expensive and “insensitive” parties is well documented. Lavish celebrations for the leader’s 90th birthday were said to have cost Zimbabwe taxpayers $1m, despite around 70% of the population living in poverty.

Rights The African Union’s main objectives include the promotion of good governance, democracy and human rights. Under Mugabe’s rule, Zimbabwe has consistently ranked as one of the worst countries in the world for civil liberties. “The police use outdated and abusive laws to violate basic rights such as freedom of expression and assembly…” according to the Human Rights Watch 2015 World Report. “There has been no progress toward justice for human rights abuses and past political violence.”

Democracy Africa is home to half of the world’s longest serving leaders, including Mugabe, who was sworn in as Zimbabwe’s president for the seventh time in 2013. Protests against veteran leaders have recently flared in Democratic Republic of Congo and Burkina Faso, when president Blaise Compaore was forced to step down after a failed attempt to extend his 27-year rule. Zimbabwe’s first lady, Grace Mugabe, has indicated she may try to succeed her husband as leader one day.

Resources In his acceptance speech for his new role as chairman, Mugabe spoke of the need to guard Africa’s resources against foreign exploitation. Zimbabwe’s Zanu-PF party was accused of siphoning millions of dollars in profits from state-owned diamond mines to finance Mugabe’s re-election campaign in 2013. Officials deny the claims.

“It’s [obviously] not possible that women can be at par with men.” Robert Mugabe, AU Chair http://t.co/9cQnjdlMUn pic.twitter.com/Mlue1Gaa2i

— Minna Salami (@MsAfropolitan) January 30, 2015

Women’s empowerment is the theme of the African Union summit being held in Addis Ababa. In an interview with Voice of America, Mugabe said it is “not possible that women can be at par with men.” It was unclear whether he was endorsing the status quo, or lamenting the lack of opportunities for African women. Either way, in a continent where gender discrimination remains widespread, it’s not the best choice of words.

Conflict Another of the African Union’s vows is to promote peace and stability across the continent. Mugabe and his associates are subject to EU and US sanctions following Zanu-PF’s victories in the 2002 and 2008 elections, which were marred by allegations of vote-rigging, violence and intimidation. Mugabe denies any wrongdoing, and accuses the west of trying to encourage regime change.