In Nigeria, internet shopping is not all that it might seem. Take Sheffy Bello-Osagie’s recent purchase of a hair product. Instead of punching in her card details online, she emailed the seller for account details. Then she went to the bank to deposit the amount in cash.

“The only thing I buy online in Nigeria is airline tickets, and that’s because the walk-in option isn’t exactly appealing,” said Bello-Osagie, referring to the chaotic queues that are inescapable for most people in Nigeria.

Forecast to become the world’s fourth most populous nation by 2050, the country has a growing middle class and a thriving consumer sector. But parallel online growth has been stifled by deeply rooted fears about online scams.

Rolling Stone magazine won’t allow Nigerian addresses to access its site, and Apple won’t allow Nigerian-issued credit cards to buy its products online – for fear of being scammed. PayPal, the world’s biggest online payment processor, refuses to operate in Nigeria.

So Nigerian dotcom entrepreneurs have to be creative. Sim Shagaya, who hopes his company, Konga.com, will become Africa’s answer to Amazon, has an unusual solution: once orders are placed online, he sends out an employee on a motorbike or tuk-tuk to collect the payment from the waiting buyers.

One of his collectors, Peter Nelson, said: “I have to explain to all our first-time buyers that we are not one of those fraudulent online companies who are going to disappear tomorrow.”

After several visits, many shoppers were prepared to swap cash payments for his portable card swipe machine, Nelson said. Only a minority entered their card details directly on to the site.

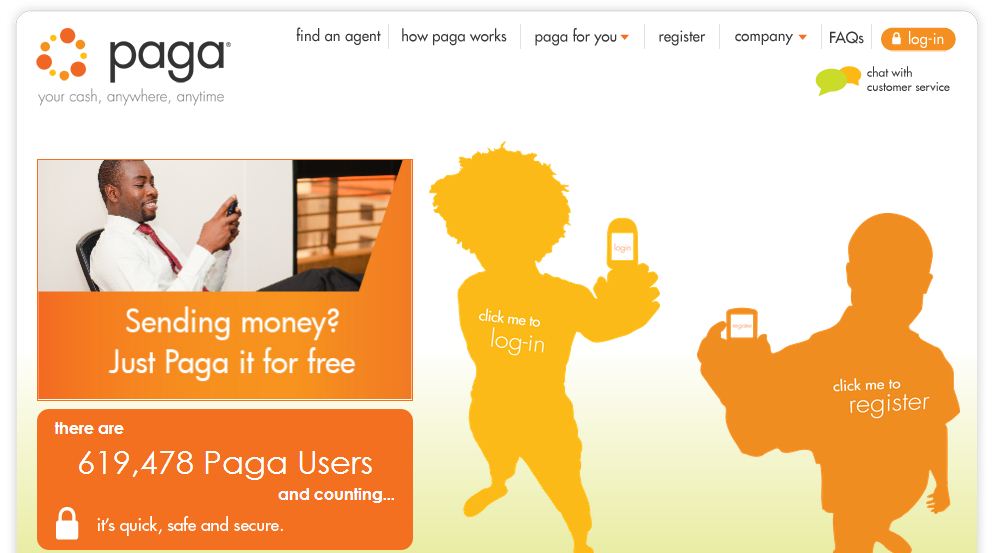

Another entrepreneur, Tayo Oviosu, is trying to build Nigeria’s version of PayPal, MyPaga. “We can sit around or we can do something about it. If other companies won’t come to Nigeria, it’s an opportunity for local businesses,” he said.

Years of soaring economic growth has failed to translate into jobs for a bulging youth population, providing a steady supply of scammers who see it as a legitimate job.

In a downtown Lagos neighbourhood, John, a Yahoo-Yahoo boy – so-called because of many scammers’ earlier preference for using Yahoo! emails – lounges outside between bouts of frenzied fraud work at internet cafes.

Shy and softly spoken, John spends his days trawling Facebook to scrape together his undergraduate fees. He finds an online “date”, then dupes her into giving him money.

But he says an average of two snares a month brings in scant reward compared with the earnings of those who work with a network of international partners, typically based in the US or Malaysia.

“They have nice cars, fine clothes, women. For me, this is just a way to survive,” he said.

As Konga.com’s motorbike riders sweep through overcrowded Lagos, they might notice a curious graffito scrawled on thousands of houses: “Beware of 419 [advance fee frauds]! This house is NOT for sale!” It is a warning against charlatan agents who “sell” temporarily vacant houses to multiple prospective buyers.

Monica Mark for the Guardian.

Comments are closed.