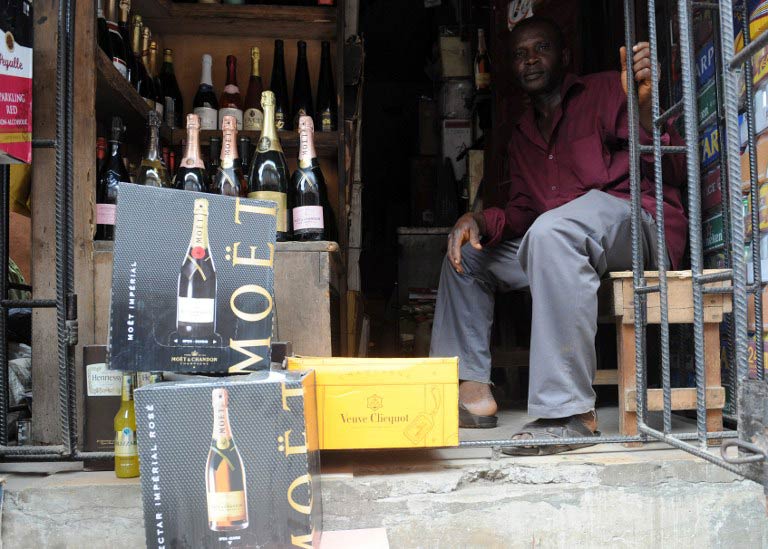

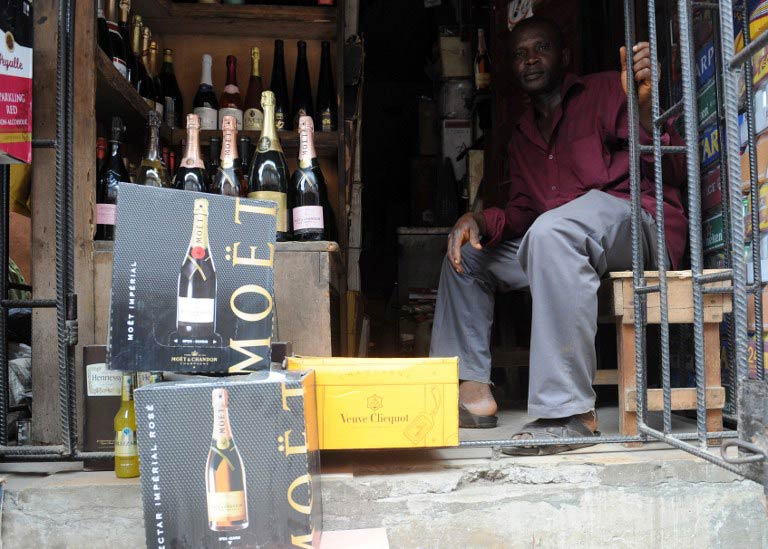

If you want an idea of what Nigeria can offer the world’s more fearless investors, raise a glass to South African supermarket chain Shoprite. Last year, its seven Nigerian branches sold more Moët & Chandon champagne than its 600 South African stores combined.

Nigeria may be best known for Islamist militants, bomb attacks, advance fee fraud and large-scale oil theft, but with a population of 170-million and a decade of annual growth rates around 7%, it also offers some outsized returns for investors willing to take the risk.

Just ask FTSE-listed Afren, whose share price shot up 9% in November when it discovered a “giant” oilfield in Nigeria, which is already the continent’s biggest energy producer.

But it is not just the traditional, grubby business of oil extraction that stands to make a mint. A youthful population is showing glimmers of a consumer boom: outside Ireland, Nigeria is the biggest market for Guinness, while brands from Porsche to men’s luxury clothes brand Ermenegildo Zegna have scrambled to open shops recently.

“It’s caught on with investors. They recognise that there’s a resemblance to what we saw in Asia [in the 1980s] and those who missed the incredible growth story [there] now have the opportunity to invest in the next growth story,” said Charles Robertson, global chief economist at Renaissance Capital.

The group forecasts that Nigeria’s GDP will hit $5tn (£3tn) by 2050, which would be on a par with Japan today as the world’s third-biggest economy. A statistical rebasing exercise next month – in which the base year for calculating GDP will be changed from 1990 to 2008 – could lead Nigeria to rival South Africa for the spot of the continent’s largest economy, with a value of close to $400bn. That would mean the economic output of Lagos, the vibrant commercial hub, alone overtaking Ghana.

Despite a decade of breakneck growth, two-thirds of Nigerians still endure crushing poverty.

After decades of false starts, Nigeria is slowly addressing its feeble electricity generation. It still produces only enough to power one vacuum cleaner for every 25 inhabitants.

“Nigeria cannot be ignored any more as an investment destination, but I’m not convinced [the Mint group – four countries identified as emerging economic giants, the other members being Mexico, Indonesia and Turkey – is] where it fits in,” said Samir Gadio, an emerging markets strategist at Standard Bank.

“If you take a closer look, Nigeria is the least developed, trails in terms of manufacturing base and displays limited economic diversification.”

Gadio said that the government relies on oil for up to 80% of its income. Shocking education levels – especially in the north, where one report found only a fraction of 16-year-olds could add up two numbers – have provided a way in for the Boko Haram Islamists. The attacks have sometimes shut down swaths of the north, prevented truck drivers from delivering goods there and prompted traders to flee south.

Along the southern shores, too, where 2m barrels of oil are pumped each day, militancy has increased amid anger as decades of oil wealth have failed to trickle down to people living in the heart of the oil industry in the Niger Delta.

Corruption and lack of transparency pushed Nigeria down nine places to 147 out of 189 countries on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index this year. Business people say local oligarchs have such a stranglehold on most sectors of the economy that it is impossible to operate unless you “know someone”.

“If you don’t have the right person holding your hand in this country, you’re going to get your fingers burnt,” said the director of a multinational food brand.

But some see potential progress from a low base.

“The challenges we have here, if you look at them differently, they’re actually opportunities,” said former bank chief executive officer and business magnate Tony Elumelu. “For example, infrastructure is a limiting factor but it’s also an opportunity for investors.”

His gleaming glass and chrome office overlooks the leafy Lagos suburb of Ikoyi, which nicely sums up how Nigeria’s economic growth has failed to radiate. Tucked behind high walls, there are more millionaires living in this part of Lagos than anywhere in Africa, and most cities in the world. But the potholes are some of the city’s worst and flooding caused by blocked drains quickly turns roads into rivers, where sometimes barefooted fruit-sellers can be seen wading through with baskets on their heads.

Clearly, there’s a lot that needs doing – and no doubt plenty of money to be made doing it.

Monica Mark for the Guardian

Comments are closed.