The tipoff late one night wasn’t unexpected. Since the crime of “aggravated homosexuality” had come into force in the Gambia in October, Theresa had been living in fear. Then a friend who worked for the country’s notorious police force warned her she would be targeted in a raid in a few hours’ time. Theresa’s crime was being a lesbian.

“I wasn’t surprised, I was expecting it anyway because the president has said many times he will kill us all like dogs,” she said. “But I was really, really scared. My friend said, if you don’t go now, it will be too late.” By dawn, Theresa was on a bus out of the country with her best friend, Youngesp, both of whom agreed to speak only if their real names were not used. The two have joined a growing number of people whose lives have been upended by anti-gay laws that trample on an already marginalised minority in west Africa.

That they ended up seeking refuge in neighbouring Senegal, where being gay or lesbian is punishable with five-year jail terms, points to the particularly dismal situation in the Gambia. Its politicians have long and publicly railed against homosexuality, with the tone set by President Yahya Jammeh, who this year labelled gay people “vermin”.

In a heated televised statement, the foreign minister announced last weekend that the Gambia would sever all dialogue with the European Union, which has cut aid over its human rights record and criticised its anti-gay laws. Bala Garba Jahumpa said homosexuality was “ungodly” and against African tradition, and that the Gambia would work with other countries on the continent to oppose it.

“Gambia’s government will not tolerate any negotiation on the issue of homosexuality with the EU or any international bloc or nation,” Jahumpa told state television. “We would rather die than be colonised twice.”

An outcry from western nations over the treatment of lesbian and gay people has often provided fuel for anti-western rhetoric, and sometimes obscured budding homegrown movements for sexual freedom. The African Commission has passed a bill to protect gay and lesbian people against violence and other human rights violations, and gay rights groups are emerging from Botswana to Côte d’Ivoire. But progress is painfully slow. Jammeh, a former soldier who has ruled the Gambia for 20 years, signed the new law against “aggravated homosexuality”, extending the maximum jail terms from 14 years to life. Targets include “serial offenders” who have gay sex, and disabled or HIV-positive people in same-sex relationships.

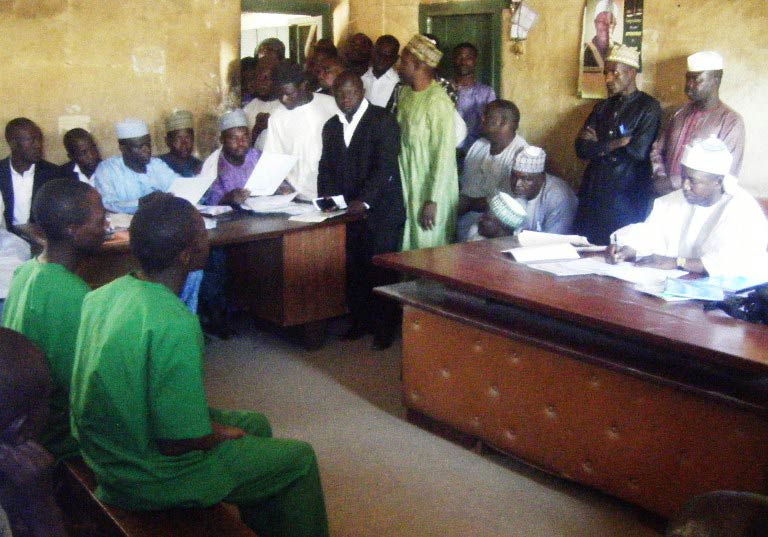

“Detainees have been told that they have to confess to their homosexuality or they would have a device forced into their anus or vagina to test their sexual orientation,” François Patuel, west Africa campaigner for Amnesty International, said of a crackdown that followed the legislation. At least 14 people have been arrested in the past three weeks, including a 17-year-old boy, and have been held in cells with no windows or lights, according to Patuel.

Campaigners are battling a wave of homophobia sweeping a continent where being gay is typically considered an illness at best. Last month, Chad looked set to become the 37th African country to outlaw homosexuality, while earlier this year Nigeria hardened its anti-gay rhetoric with a populist law that led to stonings in some cases. Some gay people have scattered to neighbouring countries, but exile in west Africa hardly means a haven: only two of the region’s 16 nations have enshrined gay rights.

Neither Theresa nor Youngesp can shrug off the totalitarian shadow of the Gambia. Though their meagre savings are dwindling, they dare venture out only to beg for food or money, convinced secret police from the Gambia will hunt them down. News from home is grim: six of their friends have been arrested and, they believe, tortured into giving up other names. Last week, security agents turned up at Youngesp’s aunt’s house and told the terrified woman they would kill her niece if they found her – a chilling echo of Jammeh’s own vow to slay any citizens attempting to seek asylum abroad for sexual persecution.

“I just want to leave Africa to go somewhere I’m not judged all the time,” Theresa said. “But I have to speak out because my friends are still in Gambia, and I really want them out.”

Ethan, a gay Nigerian using a pseudonym, is also beginning to speak out. He said depression kicked in at the age of nine when he realised he was gay – and his family would hate him for it.

“I have spent most of my life living in fear. [Recently] I saw a video at an online news site where two suspected gay men were being beaten to death with planks of wood; their blood splattered on the ground. Kids were among the onlookers. No one did anything to stop their murder.”

A friend had advised him to “lead a sexless life. [But] I’m sick of hearing this homophobia and hiding. I’m speaking out because keeping quiet hasn’t done us any good,” he said defiantly.

Monica Mark for the Guardian Africa Network