African central banks are currently burning through their foreign reserves at a rate faster than any other in the region in a bid to shore up their currencies, but going by recent events in Asia, they are likely to soon throw in the towel and relinquish control of their exchange rates altogether.

Thursday’s move by Kazakhstan, central Asia’s largest crude exporter, to abandon its currency peg has intensified speculation that authorities in Africa will devalue or halt intervening in their foreign-exchange markets.

Commodity-dependent nations such as Zambia and Ghana are struggling to cope with currency declines of more than 20% against the dollar since January, as global commodity prices tank. Bloomberg’s Commodity Index tumbled to its lowest this week since 2002; South Africa’s rand touched 13 to the dollar this week for the first time in 14 years.

Gold is traditionally the investment of refuge when currencies are volatile, but this year, even gold has not been spared the commodity plunge. Still, beyond the doom and gloom, there are still some opportunities to shield your savings from being decimated.

There are some potentially “depreciation-resistant” investments that a smart African investor can put his/ her money in:

Sari

(Photo/Sandra Cohen-Rose/Flickr).

The sari is the most recognisable traditional Indian dress for women. It’s six yards of rectangular cloth, often brightly coloured and elaborately embroidered. The sari is an important part of Indian culture, worn by grown women who have come into their own, writes Shikha Dalmia in Forbes.

Africa has a large Indian diaspora, particularly in the east and south of the continent. Increasing “westernisation” is often feared to signal the demise of traditional attire, but this is rarely the case. Instead, traditional garments actually become more elaborate and expensive, because they are now only worn on special occasions. Some saris are even embroidered with real gold thread and rough diamonds, and can retail for up to $10,000.

According to one online retailer, the margins for selling saris online can go up to 200% compared to 60% in general clothing and apparel.

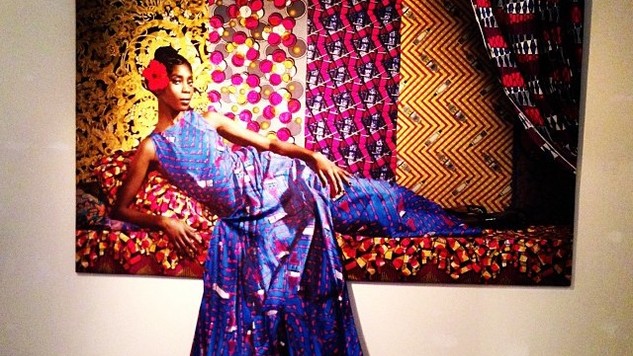

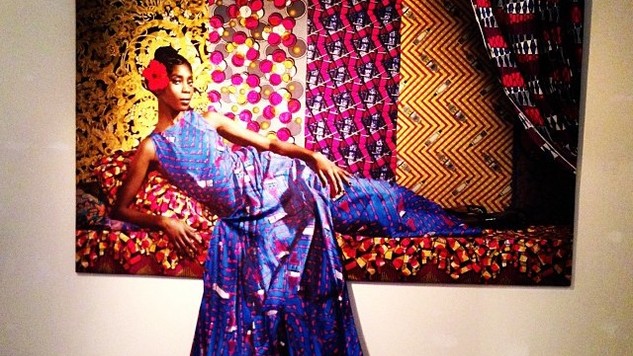

“Traditional” African fabric

(Photo/Marcdubach/Flickr).

What we loosely refer to as “African fabric” goes by different names around the continent, but it is recognisable by its bright colours, bold patterns, and boxy geometrical designs.

The most successful brand in the market is Vlisco; the Dutch company was acquired by British private equity firm Actis in 2010 for $151 million, and has transitioned from a retailer of fabric to a fully-fledged fashion house, releasing 20 to 30 designs every few months to outpace the Chinese imitations that have encroached the market.

As is the case with saris, “westernisation” makes jeans, trousers, shirts and blouses everyday attire, so African fabric such as Vlisco’s increases in status and desirability – more so the “original” wax print – used to make elaborate outfits for church on Sunday, gifts for relatives, or, simply to hoard.

Vlisco has been retailing in Africa for more than 100 years, and has survived all kinds of turbulence in Africa’s political and economic history. In 2011, Africa generated 95% of Vlisco’s $250 million in net sales that year.

Single malt whisky

Whisky for sale in Edinburgh. (Photo/Petyo Ivanov/Flickr).

If you’re willing to wait a few years for your investment to mature, whiskies are known to fetch extremely high prices at auctions across the globe – particularly rare blends from renowned distilleries.

According to the Investment Grade Scotch index that is compiled by UK-based Whisky Highland, the top 100 whiskies appreciated by an average of 440% in the last six years. By contrast, the Standard & Poor’s 500 stock index increased by 31% in the same period, and the Live-ex Fine Wine 100 Index dropped by 2%.

And it’s not only “old” whiskys that are valuable. The tip for an investor is to buy a limited edition whisky – particularly those that are a run of less than 10,000 bottles. It means that there are very few bottles of that particular blend around. That’s what makes them valuable.

For example, InsidersEdge.co.uk highlights Tun 1401, which was a limited edition release from a distillery called The Balvenie in Scotland just a few years ago. It retailed for £150 per bottle, and can now be sold for anything up to £2,000 a bottle – a 1,233% profit margin.

The most expensive whisky in the world is known as “The Constantine” from Macallan distillery in Scotland, according to CNN Money. In January, Sotheby’s sold a six-litre decanter of Macallan M for $631,000. In May, a 50-year-old bottle of Japanese Yamazaki single malt sold for $33,000.

These transactions are becoming relatively frequent, if not commonplace. Indeed, Whisky Highland expects 30,000 rare, expensive bottles to be sold at auction this year, a 50% increase on the 20,211 that were sold in 2013.

Cement, lorries, earthmovers…

Construction site in Ethiopia. (Photo/Simon Davis/DFID/Flickr).

Africa is one of the world’s fastest urbanising regions. In 2000, one in three Africans lived in a city; by 2030, one in two will do so. It means that the construction sector and industries that support those activities are bound to be in high demand. Cement is one example.

Old Mutual Investment Group’s African Equities Manager Cavan Osborne says Lafarge, South Africa’s PPC and Nigeria’s Dangote are all cement companies that have a strong footprint on the continent and are investment options worth considering.

“Everyone in the world wants to have a house, and if they already have one they want a nicer or a bigger one. That’s what makes cement such an attractive prospect,” said Osborne.

Schools and training colleges

School laptops in Nigeria. (Photo/Carlos Gomez Monroy).

Africa is the only continent in the world that is still growing, while the rest are aging. More than half the world’s growth between now and 2050 will be in Africa. Six in every ten Africans are aged under 24 years—the youngest population of any region globally.

If the right policies are drawn up, this sets the continent up for a big “demographic dividend” windfall, as workers outstrip the number of dependents. But for that to happen, these young workers have to acquire the necessary skills, and this means that post-secondary education will be in high demand.

The gold standard of post-secondary education in Africa is usually a university, conferring an academic degree. But training and technical colleges – though marginalised in Africa – are likely to make a comeback as they are a quick win for African economies striving to take advantage of the estimated 85 million jobs in light manufacturing will be up for grabs in the next few years as wages and manufacturing costs rise in China.

Good old land

View of Kisumu, Kenya’s third largest city, from Riat Hills on the outskirts of the city. (Photo/Victor Ochieng).

If you don’t have enough money for diamond-encrusted saris and 50-year-old whisky, don’t despair. In Africa, you can’t go bad with good old land, particularly if you head out to smaller cities and towns where your initial investment is likely to be lower than in the main capital city.