“S’khokhele Nkomo, s’khokhele Nkomo! S’khokhele Mandela, s’khokele Lorryhlahla!” (Lead us Nkomo, lead us! Lead us Mandela, lead us Rolihlahla!) we sang at the top of our squeaky voices. Up and down the maize field he made us march, brandishing our little hoes for Kalashnikovs. Our commander was my eldest brother Jabu and he did not tolerate slackers. No raspberry drink or a piece of bread for lazy “gorillas”, which is how we pronounced guerrillas. This was the early 1970s in our village in the then Selukwe District of Rhodesia. My young siblings and I had no idea who Joshua Nkomo and Nelson Mandela were, but they sounded and felt extremely important to big brother and our mum. She was an extremely shy woman. In fact, this was the only time I remember her ululating in public.

After the umpteenth denial of my favourite drink, I just had to ask: “But who is this Mandela? Isn’t Nkomo what we call our cattle?”

The shock on Jabu’s face was indescribable. How could I not know? These two men were going to free us. Free all of us black people.

“From what?” my junior primary school-going-self was not bound by anything.

“From all of this! All of this!”

His arm swept across the entire universe in front of us. I nodded my not-so-small head. That sounded simple enough. If anyone could liberate me from hoeing the maize, carrying firewood each Thursday and fetching water from the brook too early in the morning in June, then that was alright. Nkomo and Mandela peered at me every day from Jabu’s little notebook. They had to be kept hidden in case the police and our father discovered them. Father did not like any talk of politics in our family.

Forward to the early 1980s. I was now in secondary school. The name Nkomo had become synonymous with political ‘dissidents’; bad losers who wanted to prevent the rest of Zimbabwe from enjoying their independence. The mass media said Nkomo was bad, our lecturers at university also said he was a dissident. Jabu had already given up asking Nkomo to lead us anywhere, and was focusing on his football career instead. It was said Nkomo was not the one who had led our armed struggle for independence and freed us Zimbabweans, but the other one. I had never heard of this other one in the 1970s. We certainly didn’t sing about him on mummy’s maize patch.

Mandela was still around though, this time in colour! There was his smiley face, with the trademark dharakishon (hair parting), on his head. I learnt he was in prison. Suffering to free the people of South Africa. A few dozen of them were in my class at the University of Zimbabwe. They told me their stories. Sechaba’s father had been killed in prison, Linda’s mum beaten to death after a demonstration, Hlubi’s brother believed kidnapped and or killed by the police.

I cried each time I watched a play put on by the drama department. I read the news, books and watched television shows about Mandela and the other freedom fighters all for myself. This time I could toyi-toyi with meaning, not just because I was afraid of missing out on raspberry juice. We marched in solidarity with the youth of South Africa on June 16. Mandela’s birthday was a key feature on my calendar. On Africa Day we held vigils in Africa Unity Square in Harare. On October 7 1988, I almost lost a limb pushing and shoving to get into the stadium for a human rights concert held to call for an end to apartheid. Bruce Springsteen, Tracy Chapman, Sting, Peter Gabriel and Youssou N’Dour performed. I voraciously read every speech and watched every bit of footage of Mandela’s wife, Winnie. I liked her wigs, which looked exactly like my mum’s. She spoke fearlessly. Beautifully. I admired her. Sometimes I forgot about Mandela; Winnie represented him.

We Zimbabweans closely followed the story of Mandela and apartheid, not just out of neighbourly curiosity. Zimbabwe supported the anti-apartheid movement, provided support and arms and gave refuge to ANC members. Just as others had done for us. As a result, there were several fatal bombings in Harare in the late 80s by South Africa’s apartheid government.

Mandela no longer felt as remote to me as he had back in my childhood. At last I began to appreciate what my brother had tried to teach me all those years ago. I rooted for Mandela and his people to achieve what we had in 1980. He was going to lead ‘us’, to freedom, and I felt led by him. The South was no longer another country.

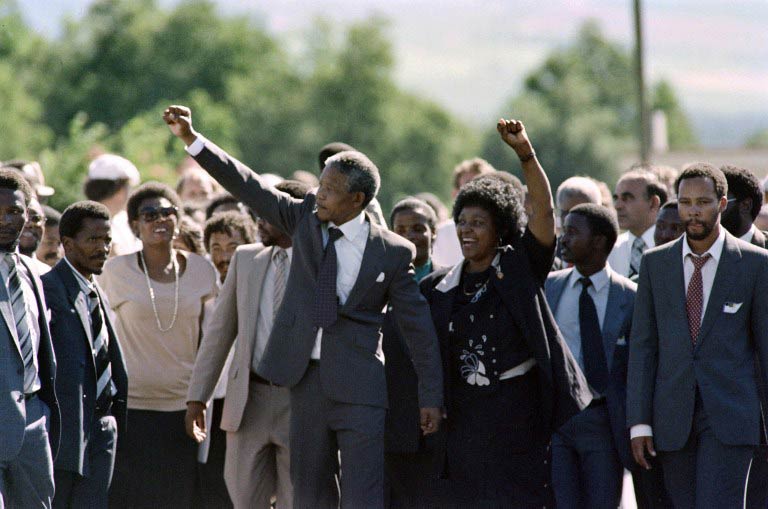

He was released from prison on February 11 1990, a day before my 25th birthday. There he was, just as I had imagined him, his face still as kind as I remembered. Winnie was at his side, in that wig! I did no work that day or the few days after that. I was free, too.

Fast forward to the 21st century. Nkomo has been dead since 1999, removed from this earth and largely airbrushed from history. He only gets dredged out when we need to use his name for present expediency.

And now, Mandela is gone. Each time I saw him and other older freedom struggle leaders of his generation on television, I simply thought of my dad who is now in his 80s. I wanted to rush and give them their bedroom slippers, a nice dressing gown, and a warm cup of cocoa. I am sure Mandela got that when he retired – unlike Nkomo who worked till he dropped, and others who don’t seem like they are ready for that warm cocoa yet.

I wish I had had the chance to sit on a cushion at Mandela’s feet and ask him: The Queen or Mrs Thatcher? What was with that hair cut? Boxing, seriously man? Did you miss Winnie? Otis Redding or Don Williams? Tambo or Sisulu, and don’t give me the political speak, which one did you really like? It would be just an ordinary conversation with an ordinary man who had extraordinary experiences.

I think of Mandela, Nkomo and other men of their generation as reminders of where we have come from. I celebrate them, their often forgotten wives and their children. These men embodied our long and painful liberation struggles. They brought us this far, they’ve had their time. Mandela gracefully handed over the reins to the next generation and stepped away from public life over a decade ago, yet he will remain in my memory and consciousness forever. He gave me, a black Zimbabwean and African woman, something to hold on to; to believe in. He was a good leader. I will always remember him and speak of him in this way to my granddaughters when they grow up; casting him not as a man with mythical or saintly qualities, but a mere mortal like the rest of us. And I’m sure they won’t raise a quizzical eyebrow and ask: “Are you sure, Gogo? Did he really do all those things or are you exaggerating?”

I was freed from carrying firewood and fetching water from miles away and, thankfully, from toyi-toying on that barren maize patch! Thirty and some years later, the blood still rushes through my head each time I watch old footage of “gorillas” singing liberation songs. I get goose bumps when they sing “Sikhokele Nkomo! Sikhokele Rolihlahla”. When I sing it now, it’s still “Lorryhlala”, deliberately, for a good giggle. I doubt Mandela would mind.

Everjoice J. Win is a Zimbabwean feminist and writer.