African app developers are getting more creative by the year, and a number of exciting apps emerged in 2014 across a variety of sectors. Major corporations are also increasingly developing their own applications, but the most innovative solutions continue to be produced by entrepreneurial developers. Here are nine of the most innovative African apps that launched this year.

Find-A-Med

Available on Android and iOS, Nigeria-developed location-based app Find-A-Med allows users to find the closest health and medical centres to them, and provides turn-by-turn directions to that centre. It also stores and tracks the basic health information of a user, and allows people to write reviews of centres they have visited. Users can also add health centres to the Find-A-Med database, which currently lists more than 5 000 medical facilities.

The app aims to makes all healthcare facilities – including dentists and pharmacies – across Nigeria accessible and searchable from a mobile, and recently won best app at the Mobile Web West Africa event in Lagos. Co-founder Emeka Onyenwe says the app is designed to help Nigerians pick and choose between the country’s many medical centres, which vary in quality.

Voicemap

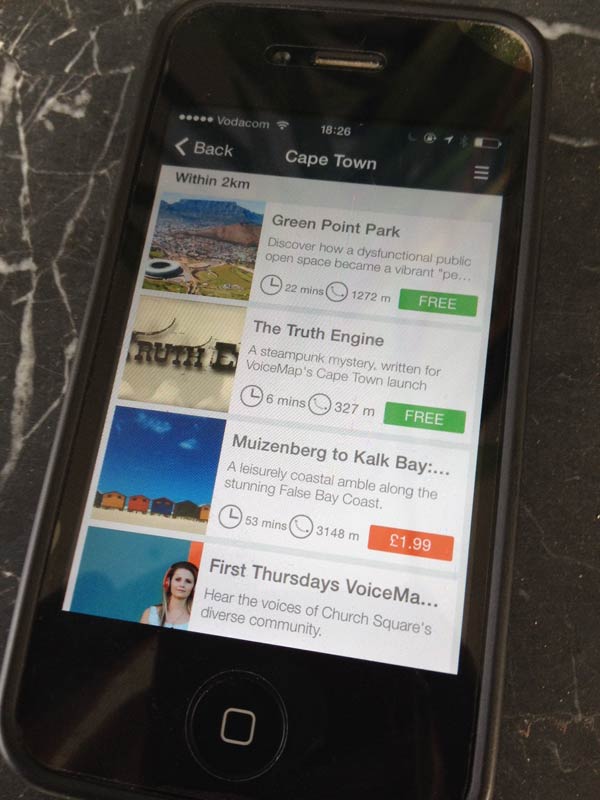

Looking to make the Cape Town tourist circuit more personal, VoiceMap allows storytellers to plan, narrate and publish their audio walking routes, which can then be purchased and downloaded by users.

A smartphone’s GPS receiver tells stories on the move, automatically starting new tracks once a user enters a radius around a certain landmark. Upon purchase, all audio files, maps and GPS data are downloaded to the phone, meaning there is no need for a mobile data connection on the walk. The app seeks to provide more personal, localised audio content for tourists, while also allowing storytellers to make money out of their stories.

PesaCalc

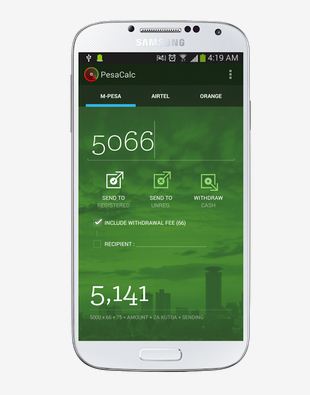

PesaCalc, released by Kenyan mobile app developers Mobile Matrix, is a free Android app that streamlines the use of mobile money services in the country, drawing contacts from both phonebook and SIM card. Compatible with all three of Kenya’s mobile money services, the app allows users to prepare exactly the right amount of cash to send including the fees, both to registered and unregistered users. Anytime there is a tariff change, users receive an automatic notification.

WumDrop

South African app WumDrop is Uber for deliveries, with a user able to request a courier, track them on a map and receive notifications of delivery, all for R7 per kilometre. The app is looking to improve the efficiency and transparency of the country’s deliveries market, and uses both professional drivers and students. Fees are split between the driver and the company. WumDrop is available via web, Android or iOS.

Safari Tales

Released in Kenya earlier this year, Safari Tales aims to solve the problem of book shortages in the country through mobile, making African children’s stories available through text, audio and visual elements. The app is interactive, and also includes stories in local languages.

The developers claim SafariTales is an education and entertainment mobile application made for Africa by Africans, aimed at children between the ages of two and nine. The company has partnered with professional storytelling organisation Zamaleo Act, experienced script writers, illustrators, animators, content developers, designers and software developers to offer a true African oral narrative experience.

moWoza

South African cross-border trading app moWoza looks to simplify the way informal cross-border traders buy and sell products, allowing traders to source products through a network of suppliers through the app.

It also allows the streamlining of the supply chain through an SMS service, while users can also negotiate bulk discounts. A taxi distribution network delivers purchased consignments. moWoza celebrated two award wins recently, winning competitions hosted by BiD Network and the Southern Africa Trust.

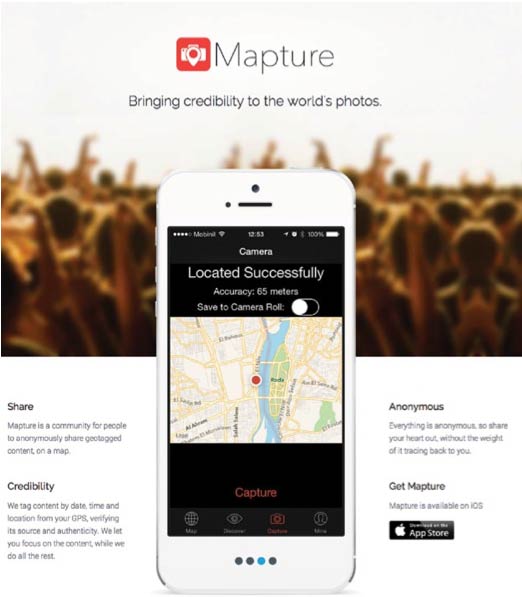

Mapture

Egyptian app Mapture is a free photo and video verification tool which aims to prevent the proliferation of misinformation and falsified images online. The app tags the location of photos through it from the phone’s GPS, making time and location of the content unalterable and verifying the source and authenticity of photos and videos. The information is then watermarked on the content, ensuring the veracity of the photo or video.

FarmDrive

Kenyan app FarmDrive aims to provide farmers with new financing options by connecting them with investors interested in funding local producers. Aimed at enhancing value addition, the app looks to improve the business practices of smallholder farmers and improve their bids for financing. The app requires farmers to form groups of five in order to collectively provide “security” for investments made into their farming unit, with each member of the team registered via their mobile phone number.

Suba

Ghanaian app Suba is a location-based, group photo album app, that allows for the creation of a group photo stream in which people can add pictures and invite others to do so. The app is a kind of family photo album for mobile, allowing multiple people to contribute and save their favourites for safe-keeping. It is available on Android and iOS.

Tom Jackson is a tech and business journalist and the co-founder of Disrupt Africa.