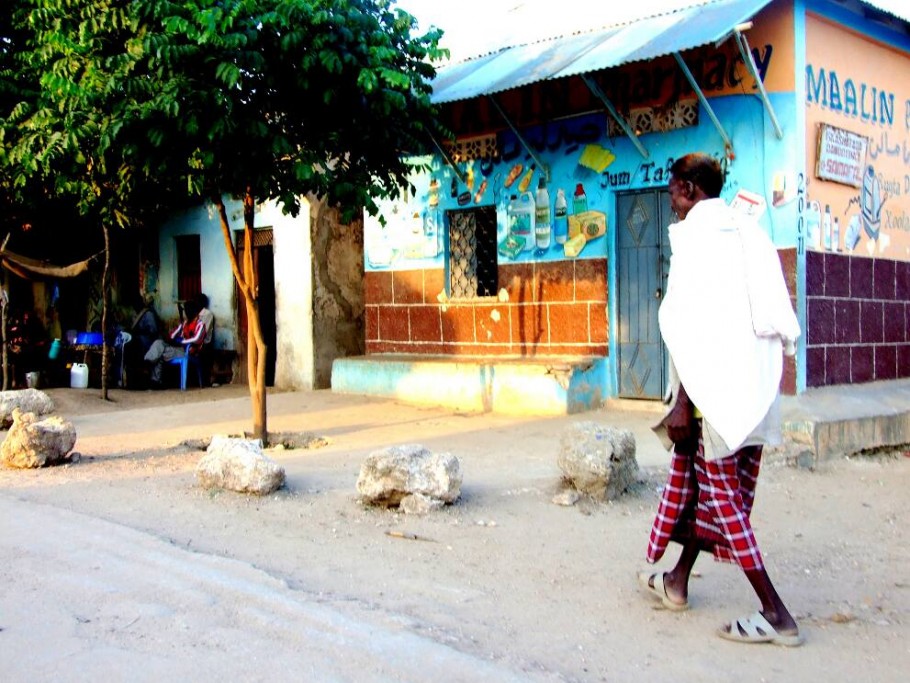

Last November, during my trip back home to Somalia, my uncle took my dad and me on a stroll around Xamar Weyne, one of the oldest districts in Mogadishu. The historic and beautiful neighbourhood was hit hard by the civil war in the 1990s, and many buildings and homes were destroyed. My father grew up here, made his memories here.

On our ‘tour’, we stopped in the middle of a street market. I tried to make a note of exact locations but after a while the streets and buildings all became the same to me. My uncle pointed out my great aunt’s house which overlooks the ocean. She married an Italian soldier during colonial times and moved to Italy where she still lives. Writing that sounds so simplistic and almost funny – “colonial times” is a period so foreign to me I can’t even conceptualise it.

My father was squinting peculiarly at a building. He told me it used to be a cinema. His cinema. The cinema he spent his Friday nights in, where he hung out with friends after a day playing soccer on the beach. I looked curiously at the building which now contained just an ordinary shop. We stood there staring for what seemed like a lifetime, until I noticed that our behaviour was attracting the attention of local folk.

These streets, with their derelict and destroyed buildings, held no meaning for me but captured so much for my father. I was amazed at the squatters who had turned these shells of houses into homes. I wondered if they belonged to them, or if the original owners were in Europe, America and Australia, safe and protected? If they returned, where would these locals go?

Imagine staying in a city through thick and thin, through pain and love, through hate and joy – and then to have those who left come back and take your home from you.

With each street turn we took, my father’s memory returned to him. A hotel there. A restaurant there. A bank there. A friend there. A girlfriend there. A relative there. A fight there. A hug there.

My imagination is good, but not that good. I could not bring his stories to life in my head, I could not turn them into a marvelous romantic saga of childhood and young adulthood. So I did the only thing I could do – I took photos.

I was also very eager to go to the beach.

“What beach?” my uncle asked.

“Lido beach.”

“On a Thursday?”

“Do people not go to the beach on Thursdays, does the beach disappear on Thursdays?” I pressed.

I knew what the problem was. My uncle suffers from laziness. I do too. But I was adamant about this and began walking in the direction of the ocean.

I fell spectacularly when we arrived, my feet unable to find a proper hold as we climbed down the rocks. A random young man asked: “Well, what did you do that for?” Yes, because I like to fall deliberately. (When it comes to asking pointless questions, Somalis are king.)

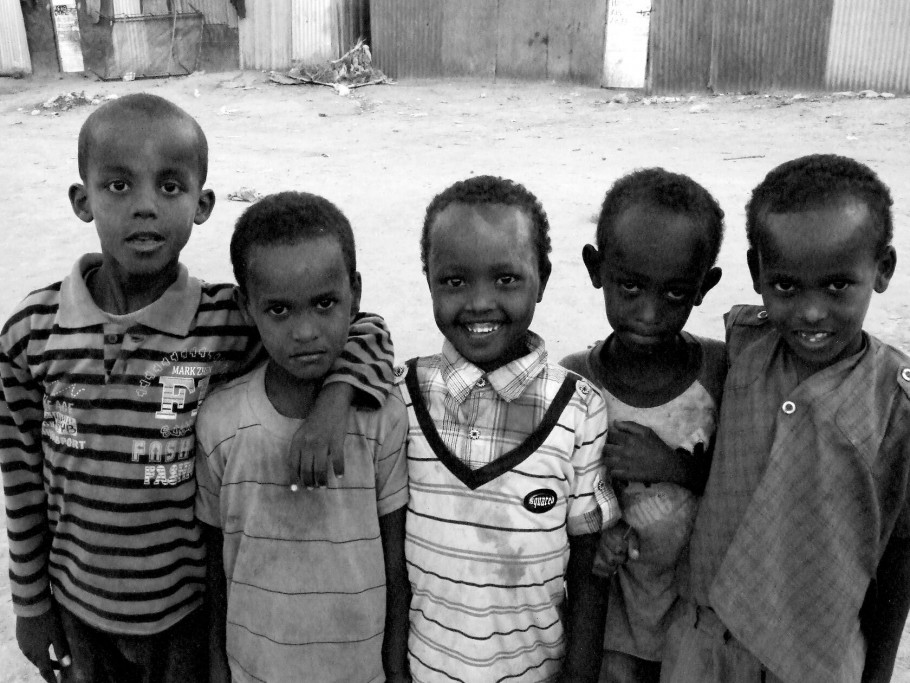

I had no grand expectations about the ocean but it did not provide any disappointments either. The sand was white, whiter than I had expected. The water was a clear light blue. There was no light bulb moment for me. No sudden urge to cry. The universe was not explained to me as I stood. This was an ordinary beach with people doing ordinary things. It was busy and noisy. The beach stretched further than my eye could see. Boys played intense games of soccer while competing with each other to get their photos taken. Then they demanded I add them as Facebook friends and tag them in the pics.

After a dip in the water, we walked up to the beach restaurant for food. My uncle scolded me when the bill came. “We’re paying for the view! Enjoy the bloody view!” I told him.

The restaurant was quiet. The benefit of being an Australian is I get to enjoy opposite summers to the Northern Hemisphere, which means hardly any American/Canadian/European Somalis were around. On some days during my trip, it almost felt like I had the whole city to myself.

Even with the cracks and the bullet holes and the decay, there is no denying the beauty of the magnifient buildings and homes that once stood on those streets and overlooked the water. Magnificent Mogadishu stood for hundreds and hundreds of years. It faltered, but it did not collapse.

It is an insult to those Somalis who never left the city when the diasporans talk of Somalia as suddenly ‘rising’ – it is the locals that kept the heartbeat and bloodline of Mogadishu going these past decades.

The stories I am interested in are those between 1992 and 2010. The current dialogue among Somalis who left the country is all about what can the diaspora do, what can the diaspora bring, and so forth. I find myself tuning out these conversations.

Really, what is more important is what we can learn about the city from those who stayed.

Samira Farah is a freelance writer and events organiser based in Sydney, Australia. Visit her blog at brazzavillecreative.com