If South Africans should be known for their predilection for taking the road less travelled – as comedian Trevor Noah once pointed out – then Zimbabweans should be known for their brilliant ideas and their less than stellar execution of said ideas.

In theory it seemed like such a good idea: replace our heavily amended Constitution with a new, fresh and updated version that would say all the right things (declarations on human rights, freedoms and whatnot). After more than a decade of bad press, an ailing democracy, political infighting and economic disaster, what better way to look forward to the future than with a new constitution?

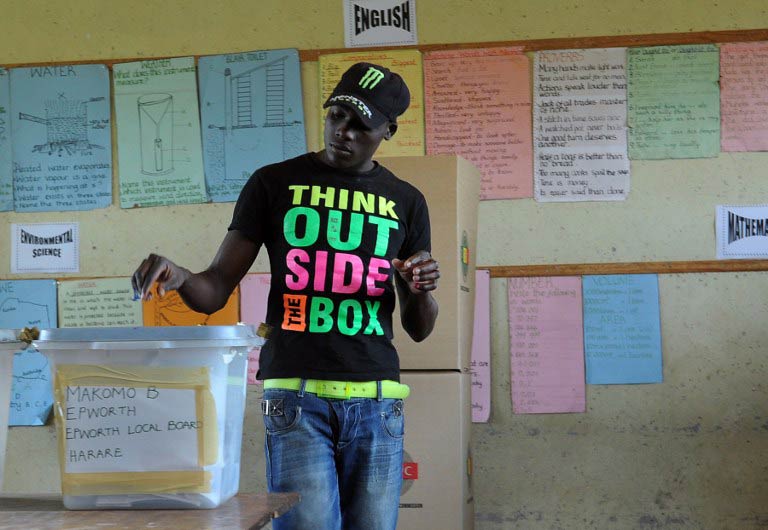

If we Zimbabweans imagined that this would herald the start of a glorious new era, then we must be disappointed. The referendum, held over the weekend, was marred by a voter turnout of less than half the registered voters, isolated reports of violence, seizure of radios from rural communities and the arrests of Prime Minister Morgan Tsvangirai’s aides. Even as the results are being tallied, the cliché rings true: the more things change, the more they stay the same.

When the process of drafting a new constitution began more than three years ago, people were optimistic. The Anything But United Government of National Unity seemed, for once, to actually agree on something. Fleets of brand new SUVs, T-shirts and flyers were spewing out from Harare to every corner of the country to harvest the dreams and desires of the people before setting them down on paper. Or at least that was the idea.

I first became aware of the draft constitution process while reading a local newspaper columnist’s piece which stated that the opposition wanted to change the flag and the national anthem of Zimbabwe. It turned out that that he had interpreted the standard declaration in the draft document – that the country was to have a flag and an anthem – as an attempt to change the existing flag and anthem. So began my love-hate affair with the document that would be drafted and redrafted multiple times to a “final draft” that would be drafted yet again to a “final, final version”.

My constant travelling during this period meant that I never got the chance to attend a Constitution Select Committee (Copac) meeting. I spoke to those who did and what they told me that at the beginning it was encouraging and sometimes amusing. “They printed the constitution on newsprint! They have enough money to buy Nissan Navaras and yet they print their sacred document on newsprint!” We laughed at that one. I tried to assure my friend Derek that perhaps the version in Harare would be printed on bond paper.

In Copac’s outreach meetings, people laid out their demands: a free and democratic state, limits on executive power and the number of terms a president could serve, devolution of the highly centralised administration that currently runs the country, and the legalisation of dual citizenship. These proved controversial but other issues tested the process to its core – gay rights sparked a firestorm when the initial draft seemed to include it and some politicians spoke out in support of the clause. The public backlash that resulted had many reversing their initial opinions and the final version of the document includes a ban on same-sex marriages. For those Zimbabweans who do not have an ‘acceptable’ sexual orientation, a friend bluntly stated: “Let them go to Europe or better yet, South Africa.” No one wanted to even dare think of our first post-independence president, Canaan Banana, who spent his twilight years in jail after he was found guilty of sodomy.

I saw the posters plastered around the country: smiling faces and the hope of a new supreme law. I hoped against hope that the document would embody the principles of a country that I would be glad to raise my children in. When the process exceeded its budget, I told myself that it was a small price to pay to safeguard the future. When the process outlived its planned lifespan I began to wonder. Drafting the document and submitting it to the parties in government who would debate it took on a life of its own as Party A refused to endorse a clause that was supported by Party B. Soon a curious stream of compromises began to take place: Party A would soften its position on issue X in return for issue Z but even that proved of limited value, and soon the entire process ground to a predictable deadlock that was only resolved when the Southern African Development Community intervened.

As the process dragged on and on, more and more people seemed to lose hope of what had started as a glorious exercise in nation-building. Clauses that had formed part of the core of their demands were modified drastically or in most cases removed from the document completely. And as I talked to more of my friends, it was apparent that very few of them had any hope that the end they had envisioned would ever come to fruition.

“Check your Facebook, Bongani, how many people do you see even talking about the referendum?”

“We all know what’s going to happen; we all know what has happened.”

And to be honest we all did. What began as a concentrated elixir of democratic ambitions on the part of the people of Zimbabwe had been watered down to 172 pages of compromises between the two major political parties. What had been the ultimate law that was to protect the rights and liberties of every Zimbabwean had turned into a close cousin of the agreement signed at Lancaster House all those years ago.

There were still those among my friends who tried their best to support it. “We should be proud that we’ve come up with this, it shows we can think for ourselves even if it’s imperfect.” This seems to be a widely shared sentiment as preliminary results show that the new constitution has been endorsed by the majority of the Zimbabwean populace.

Yet there’s one thought that continues to nag me: the generations that follow us will not only judge us for what we did, but what we failed to do.

At best, comedians of the future will think we were nothing but a bad joke.

Bongani Ncube-Zikhali is a bizarre mix of writer, poet, youth activist and a fan of Dr Sheldon Cooper. He currently lives in Paris where he is studying computer science.