As a teenager Noé Diakubama made a sketch map of Mbandaka, on the Congo river, so as not to get lost in the forest while picking a vegetable called fumbwa. “I remember never having seen a map of the city,” he says.

Thirty years later, maps of the city in the Democratic Republic of the Congo are still in short supply. So Diakubama decided to create the first one of his home city. He spent hours at his computer in Brussels, where he now lives, using Google Map Maker software and entering the streets he could recall. He hired an assistant to tour Mbandaka by bike and name the streets on a map scanned in pdf format and printed out.

Diakubama’s efforts have been replicated across Africa by scores of amateur mapmakers who have collectively pinpointed hundreds of thousands of roads, cities and buildings in remote areas ignored by colonial cartographers. This is just one example of how the digital revolution has not only caught up in Africa, but is in some respects moving faster and differently from the west.

“New technologies are in the process of transforming the lives of people,” Diakubama said. “Mobile telephony has equipped our lives by allowing communication between cities and villages without having to move; to announce a death in the family, for example.

“Mobile telephony is a true revolution in a country where the landline was restricted to a few families.”

In Africa, necessity is the mother of invention. Instead of sharing photos on Instagram or hobbies on Pinterest, you are more likely to find a service to send money to a rural relative, or to monitor cows’ gestation cycle, or for farmers to find out where they can get the best price for their goods. Technology in Africa is foremost about solving problems rather than sharing social trivia, about survival rather than entertainment – although these are flourishing too.

South Africa hosts the third annual Tech4Africa conference, in Johannesburg on Wednesday, attracting innovators and entrepreneurs from a dozen countries. Among the speakers are Sim Shagaya, a Nigerian-born Harvard graduate planning to create the “Amazon of Africa, selling Lagos’s increasingly affluent consumer class everything from refrigerators to perfume to cupcakes”. His previous venture, DealDey, which offers Groupon-style deals, is now the top-grossing e-commerce site in Nigeria with 350 000 subscribers.

The forum will also be addressed by Mbwana Alliy, the Tanzanian founder of an Africa-focused technology venture capital fund, and Verone Mankou of Congo-Brazzaville, who designed a tablet computer that sells for a third of the price of the iPad. Mankou, 26, has also launched an African smartphone, the Elikia, which means “hope” in the Lingala language.

Tech4Africa is the brainchild of Gareth Knight, a 35-year-old South African based in London. “If you remember in Britain in 2002-4, you would see the vans for ISPs (internet service providers) installing broadband,” he said. “Everyone was getting online even if they still had to use an internet cafe.

“What happened in the UK and US at the turn of the century is now happening in Africa on the mobile platform. It’s being driven by social and commercial utility needs – for example, when people want to send money. The market is much bigger than the original one in the UK and US. More and more people are going to get online in the next couple of years and they’ll want all the same things.”

In the world’s poorest continent, only one in three people has access to electricity – but far more than that have a mobile phone. Africa is the fastest growing region for mobiles in the world, and the biggest after Asia, according to the GSM Association. There are now an estimated 700m sim cards in Africa.

Mobiles overcome some of the endemic problems that have stifled progress on the continent: poor infrastructure (both in transport and power transmission), sparsely populated rural areas and widespread poverty.

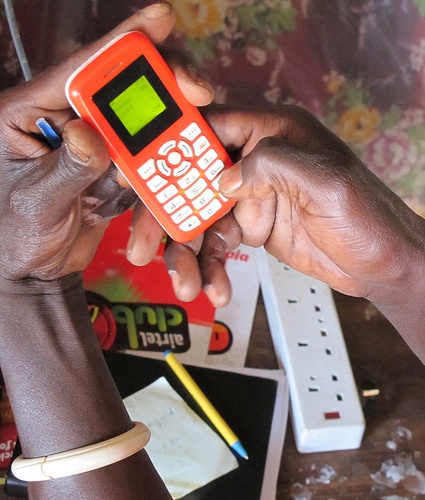

The basic feature phones that are still the most popular are vital for this environment. With small non-touchscreens, they have long battery life, though people find innovative ways to recharge, for example from car batteries.

Most have an FM radio, still the greatest communications medium in the developing world. And many have a small torch.

In east Africa, mobile money is used as frequently as paper money; the region accounts for four-fifths of the world’s transactions. With text messages it is possible to send money to another mobile that can be cashed out of the system using tens of thousands of participating agents. It is estimated that half of Kenya’s GDP moves through mobile money, mostly using the pioneering service M-Pesa, which has some 14m users.

Mobiles have fostered communication like no other technology ever before, linking villages in a split second that would previously have taken days to reach on foot or by road. Information services via text message allow farmers to learn more about best practices, market prices and weather conditions. The unemployed can subscribe to text alerts about job vacancies instead of having to travel.

Alan Knott-Craig, a 35-year-old South African tech entrepreneur, said: “It’s lighting up the dark continent. People are talking with each other. In the old days, you couldn’t talk to your family if you were a migrant worker; now you can. The next level is money. When you light it up with money, you’re giving people social freedom as well as economic freedom.”

Local entrepreneurs in hubs such as Accra, Cape Town, Lagos and Nairobi have the advantage of knowing Africa’s particular needs when competing with the Silicon Valley giants. Numerous social networks specifically for mobiles have sprung up, offering cheap or free communication for their users. Mxit and 2go from South Africa have 44m and 20m users respectively, the latter mostly in Nigeria. Others like Motribe and FrontlineSMS offer mobile communities.

According to Internet World Stats, Africa still has the world’s lowest internet penetration rate at 15.6%. Desktop PCs and tablets such as the iPad are relatively few and far between and have been leapfrogged by the more appropriate technology offered by the mobile. In conflict-riven Somalia, for example, fierce unregulated competition has made mobiles affordable and prevalent, whereas internet penetration stands at 1.14% of the population.

Among Africa’s broadband-linked minority, Facebook and Twitter, blogs and online magazines, music and video sharing sites, are thriving. That includes the political realm: atrocities that might once have been hidden by an authoritarian regime can be quickly exposed to a global audience, while the follies of leaders are held to scrutiny and mockery as never before. Shrewd politicians such as Rwandan president Paul Kagame have created their own accounts to remain connected and avoid the kind of mass mobilisation seen in the Arab spring.

“The mobile is going to bring in a huge amount of transparency and information sharing that Africa has never had before,” said Knight. “Socially and politically, that levels the playing field. People are not going to be able to say things that aren’t true; propaganda won’t work any more.

“I strongly believe this is the time when technology can make the most difference in people’s lives. There are five- to nine-year-olds today who, by the time they are 20, will have technology so embedded that the old Africa won’t exist for them.”

David Smith and Tony Shapshak for the Guardian Africa Network. This post was first published on October 30 2012.