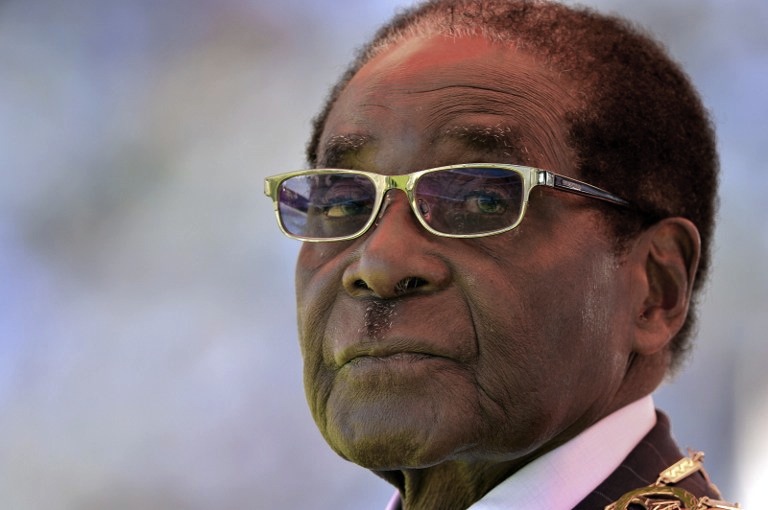

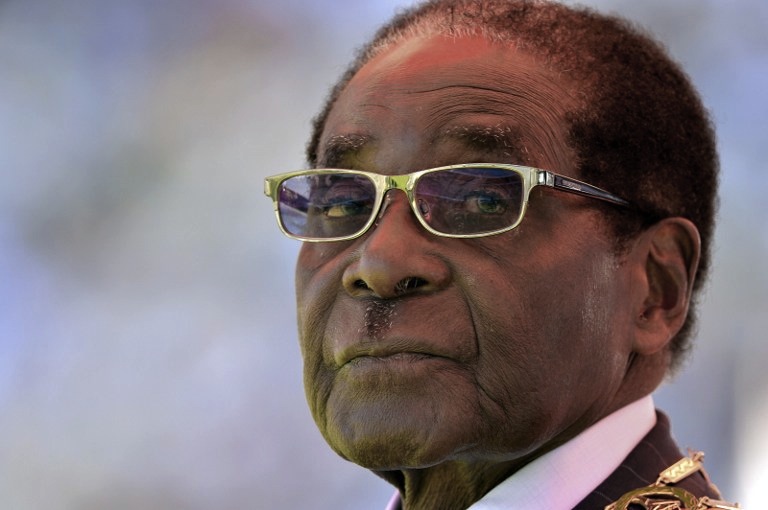

Fresh from a controversial election win, Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe is now the focus of an off-Broadway play in New York that delves into the mind of one of the world’s most vilified leaders.

The 89-year-old Mugabe, in power for 33 years, is regarded by critics as an iron-fisted oppressor who has rigged multiple elections and driven his once-prosperous nation into the ground.

But in British playwright Fraser Grace’s “Breakfast with Mugabe,” the veteran leader, who was also a hero of the struggle against colonial rule, is a depressed patient – albeit a very dangerous one.

Grace happened upon an article in the Times of London around the time of Zimbabwe’s very tense 2002 election, which Mugabe narrowly won against longtime political rival Morgan Tsvangirai, in a vote observers and the opposition claimed was rigged.

The report said Mugabe was holed up in state house being pursued by the malevolent spirit of a dead comrade and had called on a white psychiatrist for help.

Whether the article was true or not, the concept – along with the crossover between western-style psychology and African spiritual beliefs, and the enduring post-colonial puzzle – piqued Grace’s interest.

“When Mugabe was in the news, he was portrayed entirely as a monster. And my starting position was that monsters are made, not born,” Grace told AFP in a telephone interview from London.

“There is little doubt some of the ways he behaves are monstrous, but interestingly he had many of the same experiences as Nelson Mandela: liberation, prison, both suffered terrible humiliations and oppression under colonial rule.”

However, Mandela, South Africa’s first black president, is credited with uniting his country after apartheid rule.

The play has only four characters, Mugabe and his wife Grace, bodyguard Gabriel and white Zimbabwean psychiatrist Andrew Peric, all of them trying to gain the upper hand.

Peric, played by actor Ezra Barnes, first runs into the formidable Grace Mugabe, largely known as the secretary-turned-mistress who married Mugabe shortly after his first wife died and who lives a lavish lifestyle that has earned her the nickname “The First Shopper” at home.

Alternately warm and menacing, Grace, played by actress Rosalyn Coleman, goads Peric as he waits for her husband, assuring her his intentions in treating the president are pure.

“And what in Zimbabwe do you think is pure?” she scoffs. “Do what you are told or you will not be treating your patient for long.”

Mugabe, in a hauntingly accurate portrayal by Michael Rogers, sought help from the psychiatrist, yet he fights against being vulnerable to a white man, and their interactions are tense, electric and emotional.

As the psychiatrist probes Mugabe about the ghost – known as a ngozi – haunting him, the president hits out angrily with his trademark sharp tongue about Peric’s white ancestors robbing Africans of their land and their voice.

Peric, who has a keen understanding of Shona culture, is described by actor Barnes as “post-racial” and tries to defend himself. Like many whites whose forefathers moved to the continent, he considers himself African.

Their sessions bring up Mugabe’s possible demons: his betrayal of his first wife, his abandonment by his father as a boy and the death of his own child during his 11 years of imprisonment by Ian Smith’s white minority regime.

The leader of then-Rhodesia would not allow Mugabe leave to attend the funeral of his four-year-old son.

The play takes a thought-provoking look into the nature of political power, where losing it can mean losing everything.

“I am scared of the future,” the first lady admits at one point.

“Robert and I stayed with these people one time in Romania, the Ceausescus … look at what happened to them,” in reference to that country’s brutal leader Nicolae, shot by firing squad along with his wife in 1990.

However, the threat of danger for Peric is also always there.

As a result of Mugabe’s controversial land reforms, which saw hundreds of white farmers lose their land, some killed or chased off in violent rampages, so-called war veterans have camped on his tobacco farm.

Unfortunately for Peric, his association with Mugabe has a chilling end for him and his family in the play, which has been praised for its Shakespearean dimensions.

The play first appeared in a London theatre in 2005, made it to the West End and now the bright lights of New York where it will run until October 6.

“It is astonishing to find the show coming out just as another election has gone by. Things in many ways have gone backwards,” said Grace.

Fran Blandy for AFP

Comments are closed.