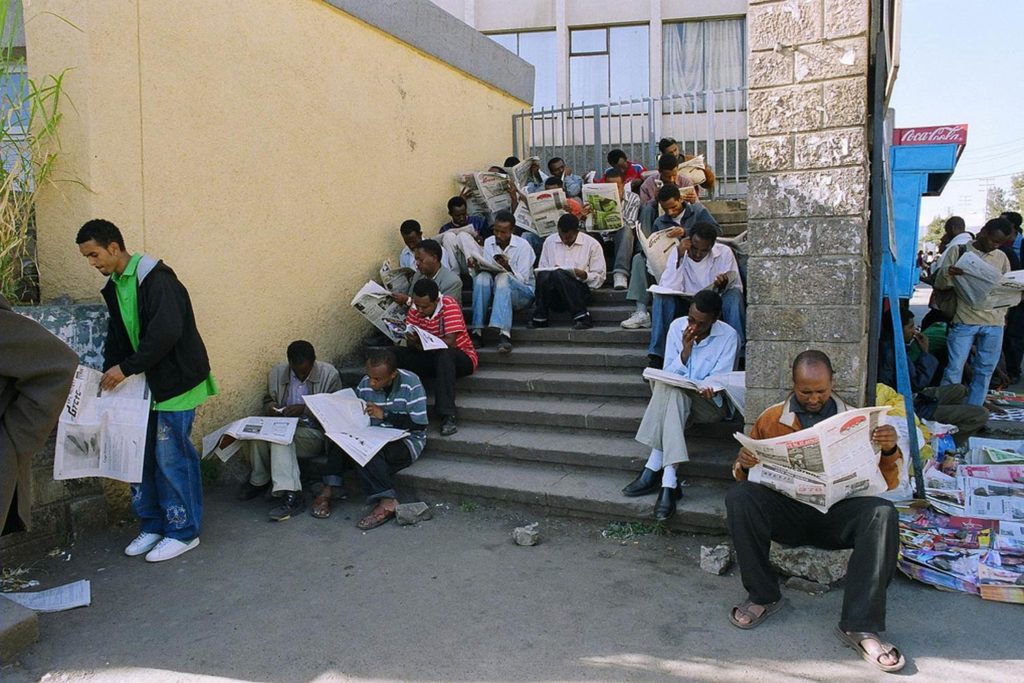

Despite an abundance of national and international newsmakers, Addis Ababa has relatively little in the way of newspapers – no dailies of note or even newsstands to offer news consumers. But don’t be fooled. This is a city of voracious readers where even the poor are indulged.

In fact, some corners of Addis are reserved for newspaper passions, Arat Kilo being one legendary neighbourhood. And by persisting, there you may stumble upon the city’s secret: consumers too poor to buy a copy of a newspaper but able to rent a read.

Arat Kilo is not only the home of the country’s Parliament building but also of flat-broke citizens with rich news-reading addictions.

“Paper landlords” offer “news seats” to readers who gather on the edge of a road, in a nearby alleyway, even inside a traffic circle. And for years, these “paper tenants” have happily hunkered down, reading a copy of a newspaper quickly and then returning it to watchful owners nearby. And even today’s deteriorating economy and “press-phobic” government has not significantly slowed

this frenzied exchange.

In a country without a substantive daily Saturday is distribution day for the country’s weeklies. That also makes it the toughest day to find an empty news seat in Arat Kilo, or anywhere on the streets of Addis.

Luckily, Birhanina Selam, the nation’s oldest and largest publishing house, where 99% of newspapers get published, is in Arat Kilo. So readers there can get news hot off the press while the rest of the city gets the paper later that day.

Major cities elsewhere in the country receive newspapers a day or two later and for readers there the cliché of journalism as the first rough draft of history seems senseless. The story is already history by the time it reaches their streets.

Unlike newspaper readers in the countryside, the poor of Arat Kilo must deal with noise. Cars blow horns hysterically. Street children shout for money in the name of God. Lottery vendors call out for customers. Taxi conductors shriek names of destinations. Yet the “renters” tune out the city’s hustle as they run up against rental deadlines. Paper landlords vigilantly act as timekeepers.

Readers dare not hold copies for more than a half hour or they will be charged more birr. One copy of a newspaper may quickly pass through a hundred readers before, late in the day, it is finally recycled as toilet tissue or bread wrap.

Now, as a rising number of unemployed people hunt for jobs through newspapers and a growing population of pensioners distract themselves with news, news seats are popular pastimes.

And this is true despite prices for newspapers doubling as a result of the rising costs of newsprint and the country’s latest round of inflation and devaluation.

Addis — dubbed the political capital of Africa because it hosts the headquarters of the African Union – is not as safe a haven for journalists as it is for journalism readers. Some international patron saints of media call the current government one of the world’s most journalist unfriendly regimes.

As more and more local journalists face threats, the number of newspapers dwindles as diminutive media houses close. Over the past few years, some two dozen journalists have fled to neighbouring countries. They’ve left behind a country hurtling towards a “no free press” zone, with few media houses willing to publish private political newspapers.

In 2010, two journalists in Ethiopia collected two prestigious awards — the Committee to Protect Journalists’ International Press Freedom Award and the Pen American Centre’s Freedom to Write Award — for their fortitude and courage working in Ethiopia as political journalists. These honours witness the way the country handles the free press.

At present only a handful of local newspapers and two handsful of local magazines circulate in Ethiopia, with a total weekly circulation that barely equals that of one day of Kenya’s Daily Nation’s 50 000 print run.

By comparison, Fortune, reportedly the leading English weekly in Ethiopia, publishes 7 000 copies a week at most. So, unfortunately, the poor – and everyone else – in Addis have fewer copies and less variety. And a nation with the second-largest population in Africa – some 80-million potential readers – registers among the fewest number of newspapers on the continent.

Ironically, in Addis you do not often see readers riding in taxis, waiting at bus stops or sitting in cafés for hours. Few Ethiopians read newspapers, magazines or books alone in public but they do banter in groups. Only a few cafés allow their verandahs to be news seats to attract more customers. On the contrary, many street-side cafés post No Reading signs next to No Smoking signs. The Jolly Bar, friendly to newspaper renters for more than a decade, now forbids customers to read newspapers inside or outside.

In Arat Kilo, however, no one expects, or can afford, to read their papers in a comfortable seat or on a café verandah. “Here citizens may stand for a while on a zebra crossing and read the headline and pass,” says Boche Bochera, a prominent “paper lord” in the neighbourhood, exaggerating how his place is overrun by newspaper tenants.

Here, stones are aids to reading as are lampposts and pedestrian right-of-ways. And readers lean against notice boards or idle taxis, transforming themselves into “newspaper warms”. The streets of Addis, like Arat Kilo, get warmer with newspapers and newspaper readers lying on them.

Nowadays, traditional newspaper vendors and peddlers find themselves challenged by newspaper lords such as Boche. From a flat stone in Arat Kilo, Boche earns bread for his family of six by renting newspapers and magazines from sunrise to sunset.

Wearing worn overalls, he spreads the day’s newspapers around him and passes copies to paper brokers, mostly kids; his “paper constituencies” may reach 300 people a day. His attachment to this task is legendary.

“I have a beautiful daughter called Kalkidan,” he says. “I named her after a magazine I lease weekly.”

And he seldom bribes community police to let him sit comfortably. “That is how I survived for the last 15 years,” he says.

When papers start to wear out with over-use, Boche splices them with Scotch tape. Then he affixes his signature so everyone knows which copies belong to him. This, he reasons, is his protection. But, he says: “Some disloyal paper tenants steal my copy and sell it somewhere else to quench their hunger.”

As the hub of street newspaper reading, Arat Kilo entertains more than a thousand people a day. Other spots are rising to the challenge.

Merkato, dubbed the largest open market in Africa, now has a place for newspaper addicts around the Mearab Hotel. When daylight wanes, newspapers rented there will be collected and resold in kiosks nearby to wrap chat, a local leafy stimulant.

Other Addis neighbourhoods, like Piassa, Legehar, Megenagna and Kazanchis have also created newspaper circles for paper tenants.

Yohannes Tekle (29) has been a regular reader of street papers for seven years. These days, especially, when a newspaper costs up to six birr (75 US cents), he rents one for 25 Ethiopian cents (which is less than one US cent).

For Tekle, a day without newspapers is unthinkable. “It is like an addiction,” he says. “Sometimes, I regret it after renting a paper when it is full of mumbojumbo news. I could have used that cent for buying a loaf of bread.”

Still, he’s reluctant to set aside the habit. “If I miss a day without renting, however, I feel like I missed some signify cant news about my county – like a coup in progress.”

Mohammed Selman, a lecturer in journalism, is a freelance writer. He lives in Ethiopia. In 2009 he won the Excellence in Journalism award for print from the Foreign Press Association in Addis Ababa. This post was first published in the M&G newspaper.

Comments are closed.