The way the Mandela story ended was the greatest comfort I could have ever been given. I could say that his funeral was the greatest gift that could have been given to the people that gave birth to him. It was the greatest tribute to Africa. Something about it was cheeky, it spoke more about the soul of the man who would become famous as the darling of the world. The Mandela who had been sown to everyone else but the Eastern Cape would choose his final resting place to be in the rolling hills of the Eastern Cape. Struggle heroes such as Oliver Tambo, Walter Sisulu and Chris Hani who all hailed from the rural Transkei were buried in Johannesburg.

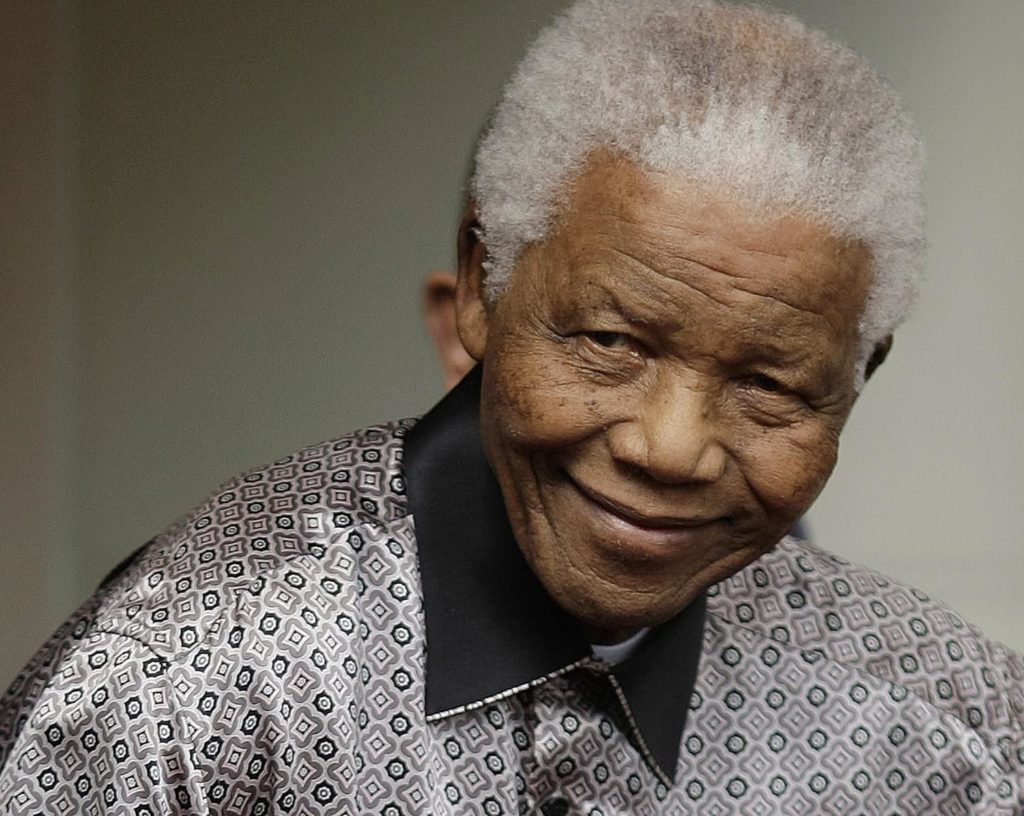

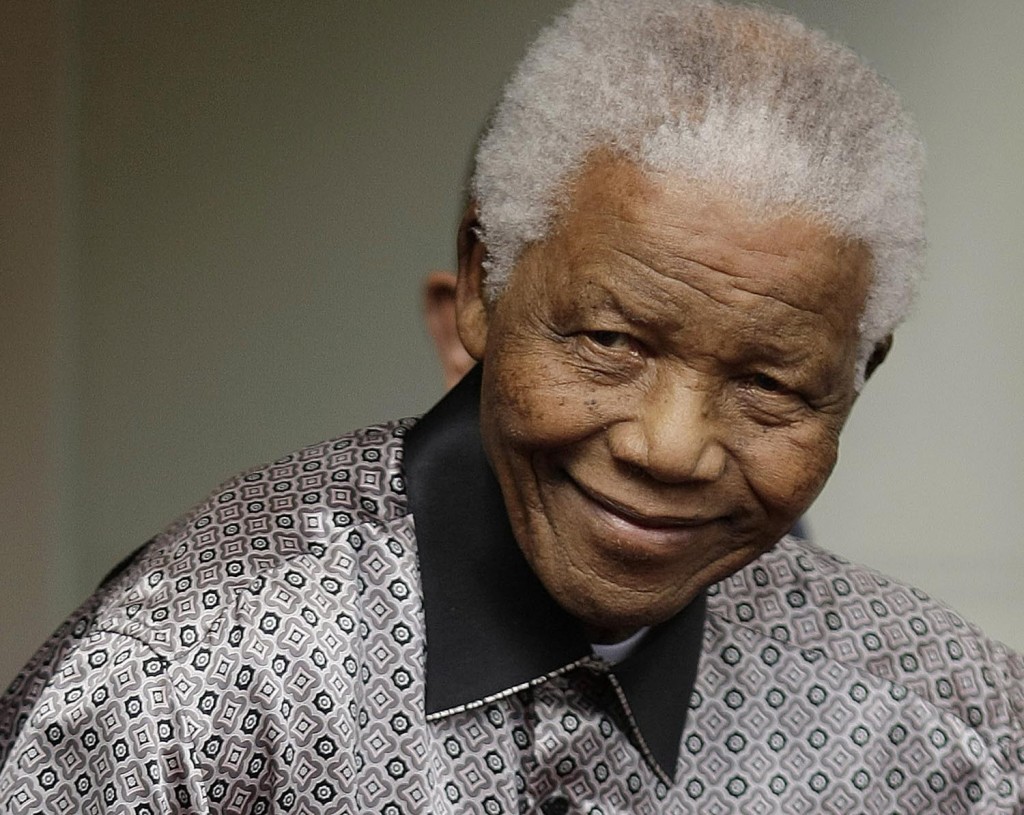

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, that great giant whose Xhosa name is often misunderstood by the international community, was buried in the region where his umbilical cord lies. This man was not like the men in his village who may have only lived in one place their whole lifetime. This man was once sentenced to life in prison far away from his people, where he was never supposed to see the hills on which he once played or walked. As a free man he became president and he was revered the world over. He has seen the most beautiful places and the worst places in the world. He was celebrated and continues to be the most celebrated human being that has ever walked the earth within their lifetime yet, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela chose Qunu as the place of his final rest. Rolihlahla means “to pull a branch”, which means to cause trouble. African languages revel in idioms and proverbs and his indigenous name is no different. His father named him on purpose. Mandela caused much trouble to the apartheid system until it was brought to an end. As a freed leader Mandela caused trouble with his own people, challenging them to be at peace in a time that was supposed to be marked by bloodshed. In Patricia de Lille’s words: “Many of us believed that we would shoot our way to Pretoria. but he [Mandela] convinced us to talk.”

Mandela famously instructed a heated stadium to throw away their weapons into the sea. He was causing trouble, the kind of trouble that is character-building and takes people to new heights and leads them to realise something greater. Mandela continued to be a trouble maker as president, he infuriated black South Africans by refusing to change the Springbok rugby emblem and by wearing a Springbok jersey at the 1995 World Cup final. That was the kind of trouble that forced South Africans to cross over old barriers and dare to see one another as people who are not playing on opposite sides but as one nation. Mandela was the kind of trouble maker that forced us to face our pain by showing us what is on the other side of the pain if we leave our bitterness behind.

How does this trouble maker end his story? How does he conclude his life? How does he continue to trouble the leaders who succeeded him? While Jacob Zuma’s Nkandla was still at the centre of national scrutiny, Mandela would be buried where the poorest people of the nation live. He would force the nation to look at the forgotten province of the Eastern Cape. He would make it most difficult for our leaders to ignore the state of the rural community in South Africa. He would add further pressure by being so important that all the leading men and women of the world would want the honour of attending his funeral in rural Transkei. He could have chosen to be buried in Johannesburg or a more accessible, developed area – one South Africa could later show off as a famous site, like we did during the 2010 World Cup. That event hardly registered in the Eastern Cape, nothing happens besides poverty in these forgotten hills. Here, in Qunu, Mthatha, former rural Transkei among the forgotten poor, where development has not yet been imagined, Mandela would host one of the largest events of the 21st century. The world would bury its hero. Qunu would be known. Mthatha would be uttered in the powerful offices of every continent and every major nation. East London would be discovered, along with the famous peaceful hills of the rural Eastern Cape and its beautiful wild coast. He would cause trouble by disrupting ordinary rural life with the arrival of the most prestigious world leaders and celebrities, cameras flashing non-stop. Qunu, despite not being built as a world stage, hosted the world’s greatest leader. Which village in the world can share that same story?

I absolutely love how the Mandela story ends… it ends where it began. It ends where economic justice is still waiting and where recognition and acknowledgement of the rural people is still pending. It ends where the battleground of colonialism and apartheid began. It ends there because it has not yet begun until it has been accomplished and completed where it began. It ends where life is romanticised by onlookers and those who live in it are forced to pack up and live in shacks in the cities because of poverty and lack of resources. It ends here, where Mandela chose to be buried among his people.

Mandela’s burial place forced the world to look at the seemingly unsophisticated simplicity he came from, the place that most Africans would identify with. He was laid to rest on the hills that taught him the greatest gift his life gave to the world, the power of forgiveness through his ability to preserve the dignity of humanity, even when a human being behaved like an enemy. Here kings, queens and presidents came to behold the humility he came from and returned to. How could such greatness hail from such a place, they must have asked?

The people of the Eastern Cape had to be onlookers as their greatest son was buried. However, they would remain there while the world would leave. They would forever know those rolling hills and have reason to keep looking. This provides all sorts of possibilities. It means that life in the now world-famous Eastern Cape will not remain the same. It indeed cannot.

Siki Dlanga is a writer and poet. She has published an anthology called Word of Worth. She is passionate about nation building, sits on the South African Christian Leaders Indaba steering committee and is a member of Freedom Mantle. Connect with her on Twitter: @SikiWrites