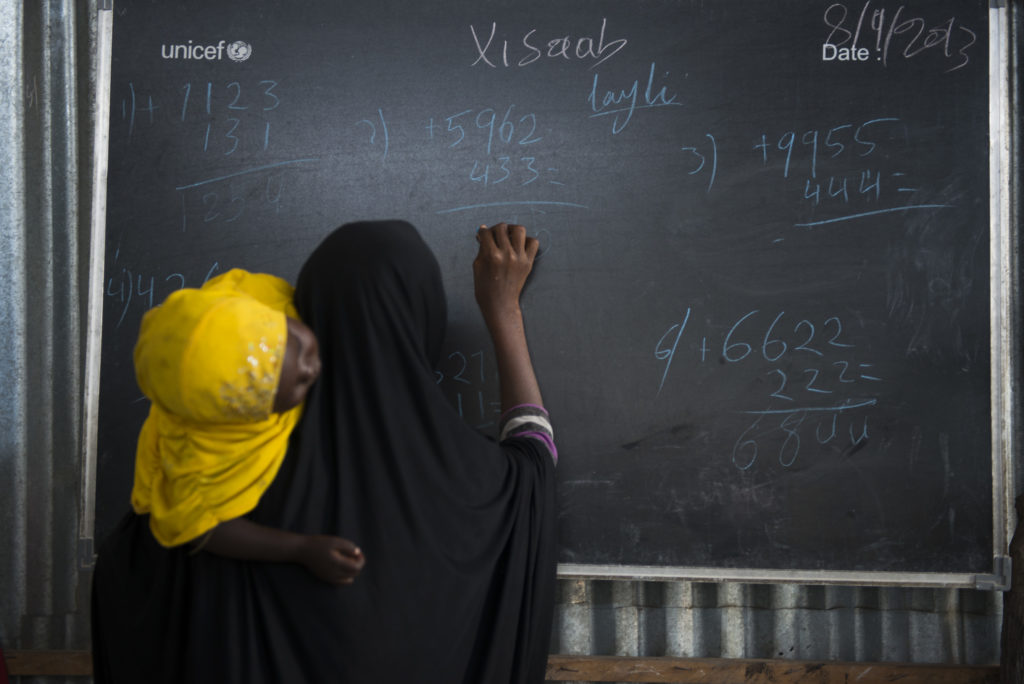

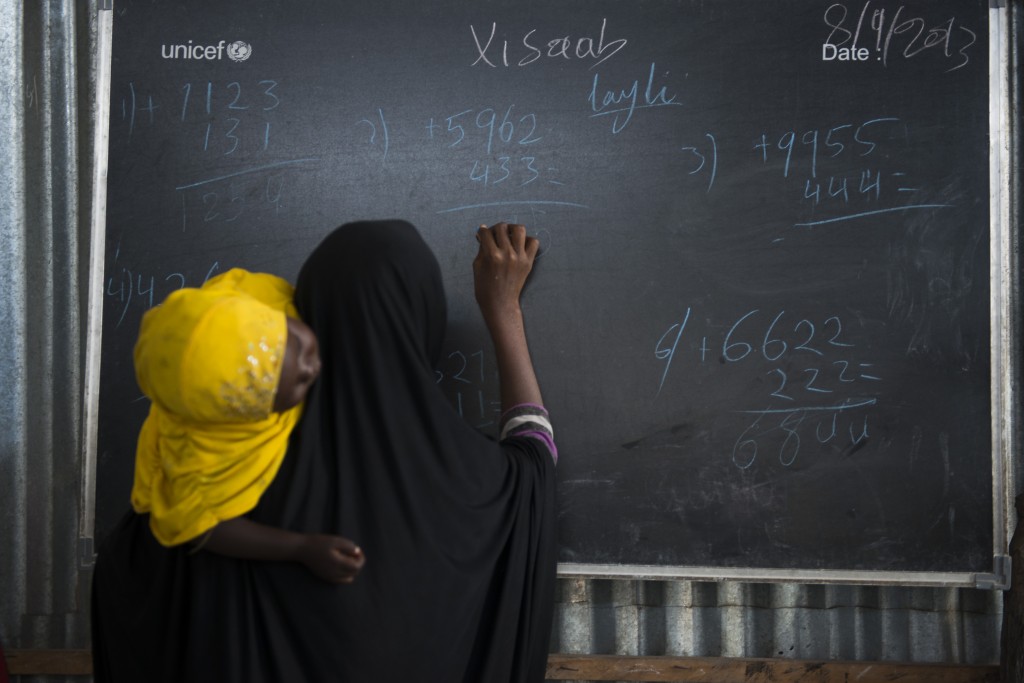

A child’s right to education is as sacrosanct as a child’s need for water, food, shelter and peace. But tragically the education system, like much of Somalia, has been virtually destroyed over the last 20 years by the terrible, senseless civil war. Now only four out of every 10 children go to school – one of the lowest enrollment rates anywhere in the world. And the numbers are far lower for girls, who are often kept at home for housework or pushed into an early marriage.

I travelled home to Somalia back in 1996, which was after only five years of civil war and already the schools had stopped functioning. At that time, I told anyone who would listen that education needed a kick-start and in the intervening years the situation has only got worse and worse. Students attend religious schools learning Arabic rather than Somali, and secondary education has been almost wiped out. So, teenage boys were attracted to the militias, like al-Shabab and other militant groups, for the food and money they provided.

When I was a young child, we lived in the Somali-speaking part of Ethiopia. There were no decent schools at that time there either. So my father took it upon himself to travel around, recruit a few teachers and personally pay them. I got to go to school – and as I was nearing the end of my primary education, as luck would have it, some missionaries set up a secondary school.

I clearly remember after a week at the secondary school thinking that this was a different world from the one in which my parents and my grandparents had grown up. This was because I could see myself through the eyes of the world to which I was being introduced. Through education, through books, I was given the chance to expand my universe far above that of my classmates and my parents. And this was all due to the exposure that I had to other languages, other cultures and other world views.

As a child I was able to place myself in the shoes of a child growing up in England or in America and my ambitions flew far ahead of my contemporaries in the same town simply because they didn’t have an education. The chances I had in the classroom quite simply made me the person I am today and gave me the opportunity to make a success of my life.

I believe that if you give any child the opportunity to read and study they will use the opportunity to take themselves – even if only in their imaginations – out of misery, out of civil war and out of strife to a higher plane.

Literacy also changes an entire community, an entire nation. It is not only schooling that is important, it is the idea of training the mind that becomes important. A child who attends school regularly behaves differently from one who is a truant and is more likely to be self-destructive and more likely to break rules.

It is discipline, patience and continuous learning that educates the mind, that makes a person produce peace: first of all within themselves and then moving that peace outside of themselves and sharing it with many, many others.

A peace process is therefore just another form of schooling – training adults’ minds to accept that there is no alternative to peace. And above all, that is what Somalia needs right now.

Nuruddin Farah is a prominent Somali novelist. He was awarded the 1998 Neustadt International Prize for Literature.

On September 8 2013 – World Literacy Day – Somali education authorities with support from Unicef launched the Go 2 School initiative, an ambitious three-year campaign that plans to provide one million children and youth in Somalia with access to quality education. Farah and Beninois musician Angelique Kidjo have urged support for it.