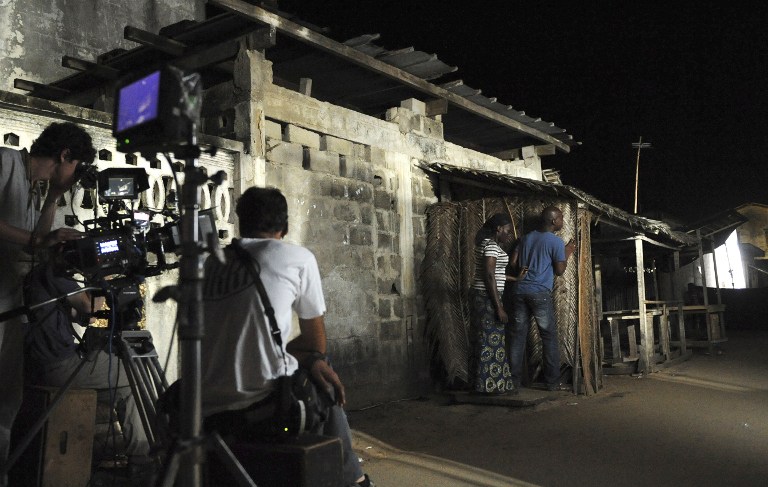

“Satché must die by the end of the day.” Such is the surrealist Senegal of Alain Gomis’s Tey (Today), a toast to life through an exploration of its morbid counterpart. The latest from the French-Senegalese director is a diasporic tale of the final day in the life of Senegalese returnee Satché, played by Saul Williams, who has been away from his community after years of living in the US.

Tey makes its American theatrical debut on October 6, at New York’s Mist Harlem Cinema, and will thereafter run in selected theaters through a “hybridised, community-driven model.”

Said BelleMoon Productions founder Guetty Felin on the importance of reaching out to smaller markets: “The hybridised model for releasing Tey is really about ‘cutting our cloth’ as my mentor often says. We know our film very well, we know who is sensitive to this sort of cinema and who isn’t. It is definitely not mainstream.”

“Neither Alain nor Saul or my company BelleMoon productions for that matter, is mainstream. This is an independent foreign film with subtitles, and black … We’re not going to break box office with it and that’s not truly our main goal. We’ve figured out who our audience or community was for the film and we are basically bringing the film to them, whether it is through a small theatrical release, college [and] university screenings or community screenings.”

OkayAfrica’s Alyssa Klein spoke with Gomis about the film.

While living in Dakar during filming did you relate to Satché’s experience in terms of diaspora-related disconnect with Senegal?

I’ve lived between Dakar and Paris for 20 years now. I was saying with this film, like Satché, this is my place, this is my present. In fact I don’t have any patriotic feeling for no country. My land is in Guinea Bissau, my fights, my dreams are in Senegal, my cinema, my family, my loves, are everywhere. Even in my little family village in Guinea Bissau, I don’t know no pure people. As soon as you understand that everybody is fighting in his own body, you deal with human beings with fundamentally [the] same type of doubts. I am a filmmaker, I’m dealing with souls, I’m disconnected everywhere, and connected everywhere, just like Satché.

What about your experience with film, if anything, made you realise the necessity of a hybridised, community-driven model of distribution? Is there anything about this film in particular that would make such a model a goal?

Maybe each time that you’re trying to make something different, I mean with a free and no marketed form, you also have to imagine new ways to reach people, especially with an African film. Africa is like another planet for a lot of people. With this film we have organised special nights – “ciné-concerts” – in theatres, in underground places, in concert halls … trying to reach all kinds of audiences … from Addis Ababa to Sydney. We had wonderful experiences and above all, it is fun to do, travel with a film just like a band in tour. And people are surprised, because this film is about us, wherever you come from. In the Q&A people talk about themselves.

Has your attitude toward death changed as a result of your work on Tey?

Yes. One of the reasons I’ve made this film was to face my own fear of death. It has become a reality. And if your death becomes a reality, your life becomes a reality. It’s a film about life.

What music would you listen to if you knew today was going to be your last day to live?

I know now, that is something you can’t predict. I have to make my life connected with my present. My last days have started 40 years ago. Every second is my last one. Today I have listened to Baloji.

Watch the trailer below.

For more on Tey read the full press release and stay up to date here.

Alyssa Klein for OkayAfrica

![A woman harvests ripe coffee berries. [Pic: Reuters]](https://voicesofafrica.co.za/media/uploads/2013/09/Coffee-grower-resized-Reuters.jpg)