Soon after dawn Bashir Bilal sat outside on his usual plastic jerry can surrounded by young girls and boys chanting Quranic verses.

Each child clutched a worn plank of wood instead of an exercise book, writing on it in Arabic script with ink made from charcoal and water.

In Somalia the Islamic madrassa is often the only education on offer, but here in the Dadaab refugee camps it is just the start. Later in the day the children are able to attend, for free, primary and even secondary school while scholarships are available for college education.

Uprooted and dispossessed, life as a refugee is tough. But for the Somalis who have for years, or even decades, called Dadaab home there are opportunities too.

Bilal (47) used to live in Afgoye, a breadbasket town 30 kilometres northwest of the capital Mogadishu. When he came to Dadaab five years ago he found better schooling options than at home where fees were high and children would often spend their days helping out on the family farm.

“Children here in Dadaab have the privilege of better education,” said Bilal. “They will bring change in Somalia when they go back.”

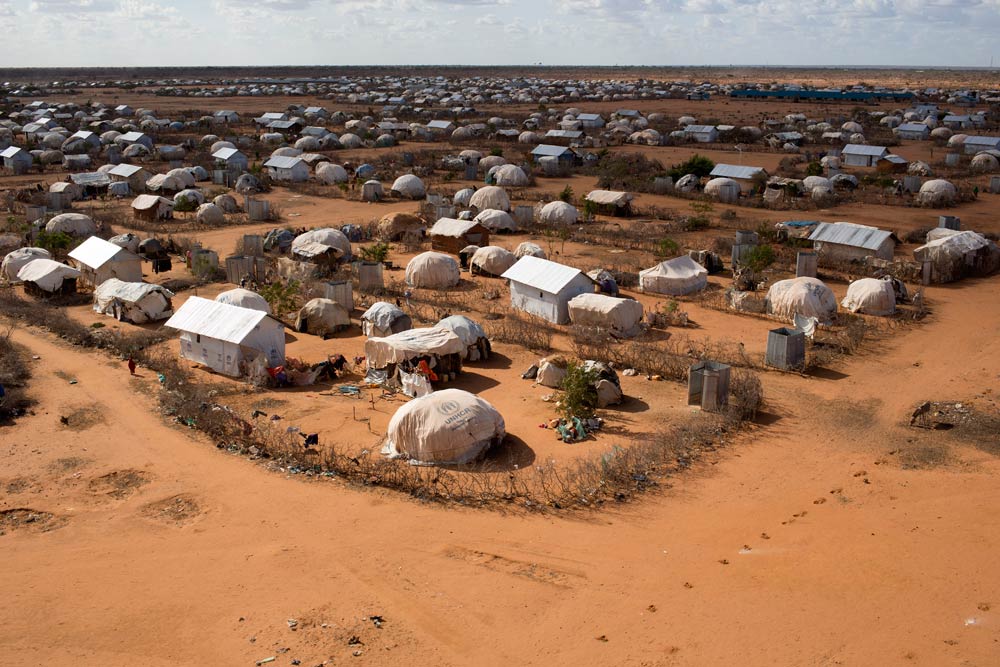

Just when they will go back is contentious. Kenya’s government has hosted refugees from Somalia since 1991 when civil war tore the country apart. Since then Dadaab has grown into the world’s largest refugee settlement, with over 350 000 residents.

Camps seen as a security threat

Kenya now wants the camps shut down claiming they are a security threat used by members of al-Shabab, Somalia’s al-Qaeda branch, for recruitment, training and downtime.

Albert Kimathi, the area’s top government official who, as deputy county commissioner is responsible for security, called Dadaab “the breeding ground, the training ground” for al-Shabab. “They use the camps as safe havens,” he said.

“I’m not branding anyone a terrorist, but quite a number of these terrorists come from Somalia. These people are one and the same,” said Kimathi.

Hopes and dreams

People living in the camps find such allegations perplexing.

Yakub Abdi left the southern city of Kismayo in 2011 after al-Shabab gunmen accused his father of being a spy, and then executed both his parents. He hates and fears the militants and so volunteered to chair a neighbourhood watch group in one of Dadaab’s five camps.

“This is not the place they are recruiting,” said the 29-year old father of two. His 260 fellow volunteers in the Community Peace and Protection Team keep tabs on new arrivals to their camp, reporting anyone suspicious to police.

“Shabab are not here,” said Abdi, but he warned that the invisible, largely unprotected border just 80 kilometres to the east, meant they were not far away either.

Despite living in temporary shelters and barely subsisting on food handouts, Dadaab is not a place of universal misery and hopelessness.

“People think there’s no life in the camps, but there is life,” said Liban Mohamed, a 28-year old filmmaker from Kismayo, in southern Somalia. “There are problems here but there are also hopes and dreams.”

Mohamed’s dream is to be resettled in the US where his mother and siblings already live, and to continue making films. For others the dream is closer to home, and nearer to being realised.

Mohamed Osman is a trained medical officer who for the last 15 years has provided free consultations, affordable drugs and in-patient treatment at his private pharmacy. He left Somalia in 1992 seeking safety and prosperity and in Dadaab, his family and business have thrived.

“Children in Somalia have no hope,” said the 42-year old father of 12 children from two wives. “My children are learning here.” He has no desire to return to Somalia because “there is still fighting there”.

A short way from Osman’s pharmacy, along flooded and uneven dirt roads, the daily delivery of khat, a herb with a mildly narcotic effect when chewed, was unloaded.

A broker who runs four pick-ups piled high with 50-kilogramme sacks of khat into Dadaab every day said he sells out his entire stock without fail, making more than 30 000 shillings (280 euros) on each truck.

In a frenzy of activity the retailers, including 43-year old Fatima Ahmed, split the sacks open on the ground sorting the vivid green shrub into kilo bunches. Prices are seasonal and low during the current rainy period, but still, Ahmed said, she buys at 100 shillings (1 euro) and sells at 150 shillings (1.40 euro) making a modest daily income. “It’s a good business,” Ahmed said.

Sellers’ profits are ploughed back into Dadaab’s thriving economy which, according to a 2010 study, is worth around $25 million (22m euros) a year. The research, commissioned by Kenya’s Department of Refugee Affairs, found that Dadaab also earned the nearby non-refugee, or host, community $14m (13m euros) a year in trade and contracts.

Mini Dubai

Each camp has its own market but Hagadera is the most established. A Kenyan official described it as “a mini Dubai”.

There are hotels and restaurants selling grilled camel meat, chilli hot samosas and spiced tea with camel milk, general stores with shelves of pasta, rice, milk powder and sugar – much of it smuggled in from Somalia and sold at a steep discount – electronics shops with the latest smartphones, narrow alleys stuffed with stalls selling new and secondhand clothes, fabrics and shoes and shady passages lined with tarpaulins piled with mangos, avocadoes, potatoes and onions.

Ali Saha, a 23-year old university graduate who runs a cyber café, said he wants to return to Somalia, just not yet.

“Education is a privilege and from that angle being a refugee is not that bad,” he said. “I should return so I can help my community in Somalia but I need to go back when my country is stable.”