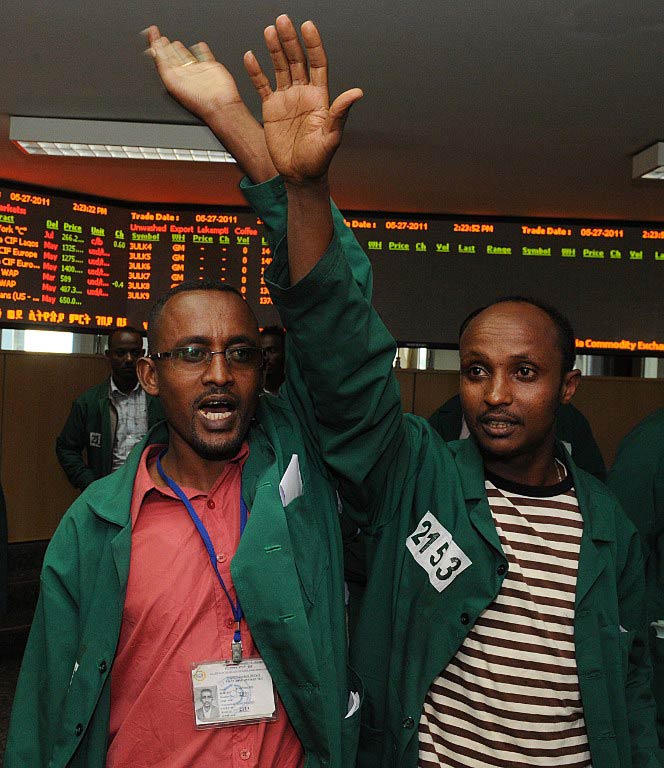

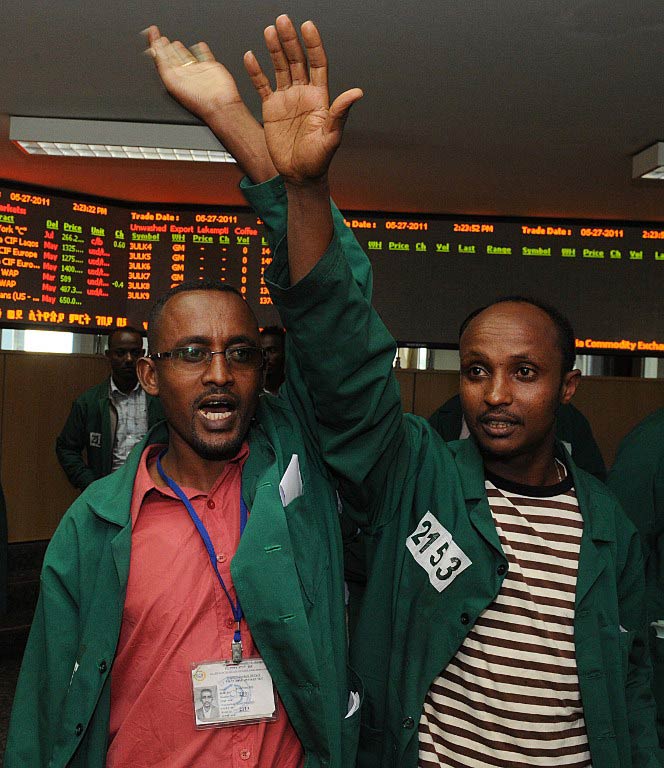

Digital screens light up Ethiopia’s small towns, from Assela and Humera to Jima, displaying the real-time prices at the country’s central agriculture market, the Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX). The ECX acts as an organised marketplace where buyers and sellers come together to trade, assured of quality, quantity, payment, and delivery.

Mohamed Abafogi, a farmer from the Jima area of Oromia state, lives more than 300km from the central market in Addis Ababa. Despite the distance, ECX provides Abafogi with the most up-to-date market information and prices, allowing him to sell his coffee beans at the nearby ECX delivery centre at a competitive price with prompt payment. Buyers collect beans directly from farmers like Abafogi at regional centres and transport them by truck to the nearest port, in Djibouti, for export.

“Today I am earning a far better income than before. I am selling my coffee to the people of ECX at a fair price. These days my children do not go to school with empty stomachs,” he said. Last year he was able to replace his straw roof with one of corrugated iron. “I am better off today,” said Abafogi.

ECX assures delivery to buyers and due payment to farmers. Seven years ago, a buyer who paid in counterfeit cheques cheated dozens of Abafogi’s neighbours. Dealers were able to dictate prices to farmers, as there was no competition.

Samuel Mochona, ECX’s communications manager, said the market had opened up trade since its establishment in 2008 by the Ethiopian government. In addition to coffee, sesame seeds, mung beans, maize, wheat and peas are also traded.

“Before ECX was established, agricultural markets in Ethiopia had been characterised by high costs and high transaction risks. With only one third of output reaching the market, commodity buyers and sellers tended to trade only with those they knew,” he said. “This helped them to avoid cheating sellers and defaulting buyers.

Through ECX, buyers are assured of a quality product, with tests conducted of both raw and roasted coffee samples, while farmers are assured of payment. ECX also gives technical support to farmers, who must meet global quality standards for their coffee to be accepted,” added Mochona.

Thirty-three farmers’ co-operatives, representing 2.6 million coffee farmers, share 15 market seats in the ECX. This gives them permanent and transferable rights to trade on the exchange.

“I can confidently say that trends in this country vividly show that ECX is successful not only in increasing the income of the poor farmers from coffee sell, but contributes to general economic development,” said Abenet Bekele, ECX chief strategy officer. “At present, however, no calculations have been made of the net benefit to farmers.”

Coffee production

Around one fifth of Ethiopia’s population depends directly or indirectly on coffee production and trade. Coffee earned almost 25% of total foreign exchange in the country in 2012/3 and accounts for 2% of GDP, according to the Ethiopian Commodity Exchange Agency, the government body overseeing ECX.

“I don’t have words to explain the stark contrast in lifestyle in my family and my neighbourhood before and after the coming of ECX. Previously, I could only afford to send one of my three boys to school as the remaining two had to work. But now all are in school,” said Abafogi. He now plans to establish a flourmill, which will be run by his wife.

“Improvements in agriculture, like ECX, can make an enormous difference in the lives of smallholder farmers,” said Dr Sipho Moyo, Africa Director of ONE.org. She further explains that providing resources like these can boost farmer incomes and break the cycle of poverty and that investing in agriculture now could help lift tens of millions of people out of poverty by 2024.

In January, ONE.org formally launched the Do Agric, It Pays campaign, based on its report, Ripe for Change: The Promise of Africa’s Agricultural Transformation, which calls on African governments to implement an enhanced CAADP (Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme) framework.

The enhanced CAADP policies were developed after a lengthy consultation process with African farmers and farmers associations from all over the continent. The package of policy recommendations include eliminating the gender gap in agriculture, developing the value chain to benefit small holder farmers, and making time-bound commitments to spending at least 10% of national budgets on agriculture investments, amongst others.

Taddese Meskela, head of the Oromia Coffee Farmers’ Co-operative, says ECX plays a pivotal role in ensuring fair prices for farmers and supplying quality coffee to global markets.

“Our members’ income is continuously growing as they are getting due prices for their produce,” he said.

Girmaye Kebede for ONE.org.

![A woman harvests ripe coffee berries. [Pic: Reuters]](https://voicesofafrica.co.za/media/uploads/2013/09/Coffee-grower-resized-Reuters.jpg)