One day in February 1977, the military government had had enough of Fela Kuti and ordered that soldiers raid his self-declared independent ‘nation’, the Kalakuta Republic. They burned down the houses of the commune. They beat up the activist and musician severely and raped many women, including his wives. They threw Fela’s mother Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, an activist and political figure who fought for women’s rights and democracy, through a window. She died months later as a result of her injuries. Fela, carried along by a wave of loss and sadness, later decided to lead a group of his followers to the residence of the head of state at Dodan Barracks with the coffin of his dead mother. His message to the Nigerian government of the day was clear: take what you have made of my home, my country, and give us back what is ours.

Felabration, the annual two-day festival celebrating the now-late Fela Kuti, was held in Lagos this week at a time when Nigeria is in the most peculiar of situations. The country is in bad shape, to be sure, but its ruins are not the same in every home. Some of us have not had our entire worlds yanked from beneath our feet. Some among us have children who do not know a time when our walls saw a coat of paint. Others merely see the worst of pervasive lack on the streets while riding in air-conditioned cars. Our Africa is indeed rising, but with a tide that has lifted some boats and sunk many others. That so many of us are buoyed while most are sinking can distort our urgency, but it is at this time that Nigerians must find the eyes to see the bleeding body that has been dropped at our front door.

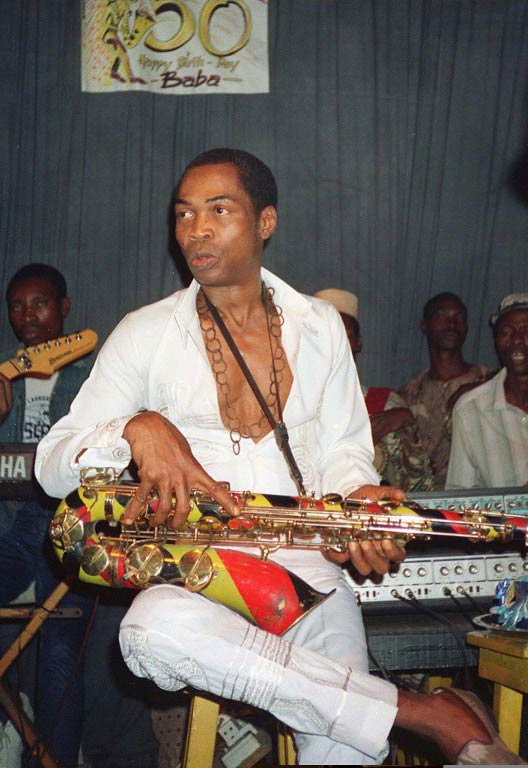

With a wildly popular Broadway musical and a movie currently being made of his life, Fela Kuti’s image and music have seen quite the resurgence in the past decade, but I do not think enough has been said about what he tells us about restoring Nigeria. He was defiantly, stubbornly, wholly himself. All parts of himself – Yoruba, Nigerian, African, black, man – coexisted in way that it simply does not for so many of us here, our language heavily-accented by the Western world that influences us. And it’s not like Fela Kuti did not have his musical influences from beyond Nigeria, like Ornette Coleman and Sun-Ra. It’s not like he was not part British himself, with a mother who was by no means conventional.

In an era where so much of our literature is besotted with culturally uncomfortable people like me whose indigenous language is clunky as metal on our tongues, Nigeria’s ever-expanding gap between the rich and poor means that, even if you did speak your language, you still may not be able to easily relate to the majority of the people around you. These are the lines that are drawn that undergird the politics of our time.

This assuredness in his identity freed Fela in a way that mine does not for me, ridding him of any longing to effect change in a nation while casting himself aside in technocratic detachment, striving to be immune to its politics. If you’re sure of who you are, sure of the strength of your core beliefs and values, then you need not fear what your environment may do to you. Best of all, you would not fear being political, and Fela was unabashedly political. He started a political party, Movement of the People. His Kalakuta Republic was an unabashedly political statement. Remarkably, through his music he was able to convey everything from observations on Cold War geopolitics and Nigeria’s military dictatorship (listen to Beasts of No Nation and Unknown Soldier) to heartbreaking storytelling (Coffin for Head of State) and reflective observations on urban life (Monday Morning in Lagos is one of my favourites).

We live in a more global world than Fela did, and I pride myself on not being bound by my Nigerianness. You’d understand, then, my hesitance at the idea that Nigeria is worth dying for. I am an educated self-sufficient young Nigerian who, by accident of family, class and network, can afford a life that a lot of people would be fortunate to have. I’m not filthy rich, mind: the cost of phone calls and internet connectivity still make me cringe; I do not own a generator set so I’m on my own when there are outages; I do not own a car so the cost of transportation in Lagos is a major reason why I hardly ever visit my hometown and adds to the cost of my grocery list every week here in Abuja. Still, I survive – even flourish – in a way a lot of fellow Nigerians do not. I get angry, but I also get tired of being angry. I simply cannot summon the reserve from which to draw on to continue to lash out over and over again.

I often envision Fela in awe, fighting back tears as he led a procession to Dodan Barracks with a coffin containing his dead mother, his steps heavy as he approached the front gate. He must have known that he would end up in prison for a long time at best or be killed at worse, and I do not know where his strength, his faith, his rage, his patriotism came from. I do know that we have to find it and give back this mangled body of a nation for what is truly ours. Just as with Fela, the worst that could happen is that our efforts fail.

Saratu Abiola is a writer and blogger based in Abuja. Connect with her on Twitter or on her blog.

Comments are closed.