Last Tuesday night, Nairobi held its first major, international commercial auction of East African art. The auction, organised by the Circle Art Agency, featured 47 works from 43 artists from six countries spanning the last four decades. In terms of sales, it was a huge success, with 90% of the works going for a combined Ksh18.5-million ($216 000).

But in a region long ignored by serious art collectors, and in a city that has mainly catered to foreign art buyers, the auction’s biggest achievement was that over half the works sold to Kenyans. Though that fact is partly a symptom of the ‘Africa Rising’ story of growing middle classes, it also marks an arrival for an unlikely city that has forged a unique modern art history.

“Kenyans like a party”

On the surface, Nairobi is perhaps a surprising art centre as it has little or no art infrastructure. The city has no renowned university art programmes and only two professional galleries, both of which operate in private homes to stay afloat and take tiny percentages so they can keep on board artists who would otherwise sell from their own studios. Kenya more broadly has no art education in government schools or significant public art installations. And beyond a few graffiti artists and political cartoonists, visual art is not on most Kenyans’ radar. The government is so out of touch with local art that it sent Chinese artists to this year’s Venice Biennial to fill the Kenya pavilion.

Yet behind the scenes, Nairobi’s art scene hums with improvised vibrancy. In slums, self-taught artists work in collectives where artists sleep, eat, and create together, pooling profits under the tutelage of an established name. More successful artists share shipping containers as studios. There are showings every week in galleries, private homes, restaurants, and cultural centres, and studios are gathering places for artists, buyers, and hangers-on.

But without a base of buyers who grew up learning about and viewing fine art, groups such as Circle Art have had to be creative in educating and building a market of locals willing to invest in Kenyan art.

“The traditional gallery sort of situation of going to a gallery and running for two or three weeks is not necessarily the best way to bring in a new audience,” says Danda Jaroljmek, director at Circle Art, explaining why they opted for an auction. “Kenyans like a party. By having a big noise, some glamour, a sort of party atmosphere, that’s perhaps a better way of doing it.”

Circle Art gives city art tours to galleries and collectives, and hosts collectors clubs to teach interested Kenyans about the history of local artists. There are ‘M/eat The Artist’ dinner parties in private homes where artists show and sell their work, and most studios are available for walk-ins whereby people can watch the artists in action and buy directly from the source. In Nairobi, art is interactive.

“It’s the story of Kenya,” says artist Gor Soudan (31) from his cramped apartment studio in the city’s Kibera slum. “The government, the banks were not working properly so M-Pesa [a mobile money service] came up to bank the poor people. So that’s the way the art scene is growing. By need and vision.”

Soudan, who was featured in the London’s 1:54 fair of contemporary African art last month, weaves human figures using metal wires from tyres burnt in riots. His home is a mini hub for local artists, and within walking distance are two other slum collectives. At one, artists weld scrap metal into sculptures and paint dreamscapes on Chinese-made plastic Muslim prayer mats.

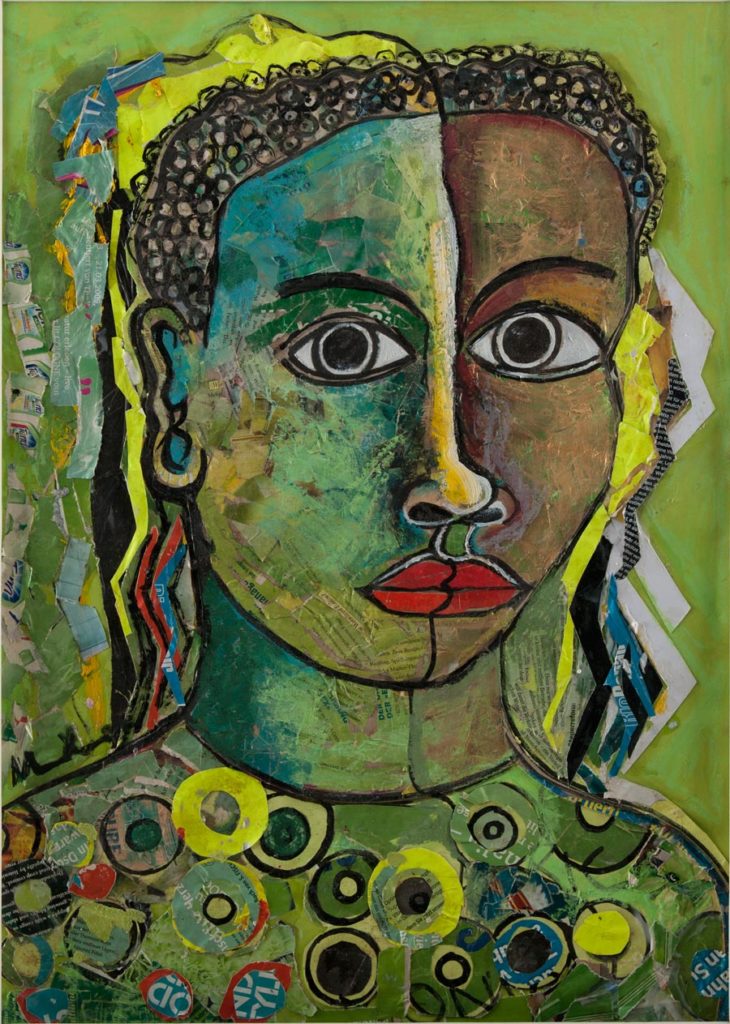

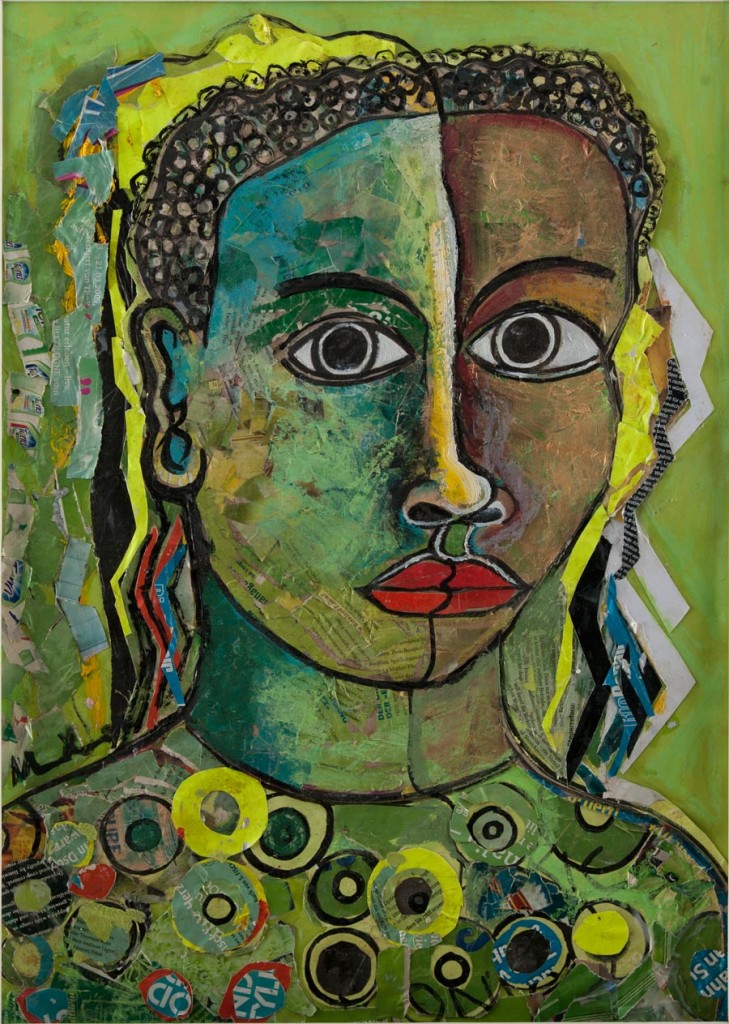

Artist Paul Onditi, whose painting Half Life sold at Tuesday’s auction for Ksh704 400 ($8 200) says the fact that these many artists have little training means they make better art. “Here is a place you get self-taughts and they gamble around,” he says. Onditi is actually one of the few here who has received some formal training, but like his fellow local artists loves to experiment, making paintings by a long process of printing digital pictures and transferring them, through a four step chemical procedure he developed, to antiquated plastic printing press boards that he covers with oil paints.

Painting politics

Kenya has long been known for its untrained but exciting artists. The ‘naïve’ movement, so called because the untutored artists never studied things like perspective or art history, dominated Nairobi’s scene for decades. Artists such as Sane Wadu, Wanyu Brush, and Jak Katarikawe painted surreal scenes of animals and rural life with expressive colours, and were marketed to foreign buyers as ‘untouched’ modern African artists.

These artists are still revered in Kenya and internationally – a six-panel painting by Wadu sold for Ksh1.5-million ($17 000) on Tuesday – but in the last decade, a new group of contemporary artists have become the big names in Nairobi. This second generation – of Onditi, Soudan, and others – is often just as untrained, but is connected through the internet to global conceptual trends. Notably, these younger artists are more eager to take on political issues now that Kenya’s public space is freer under multi-party democracy.

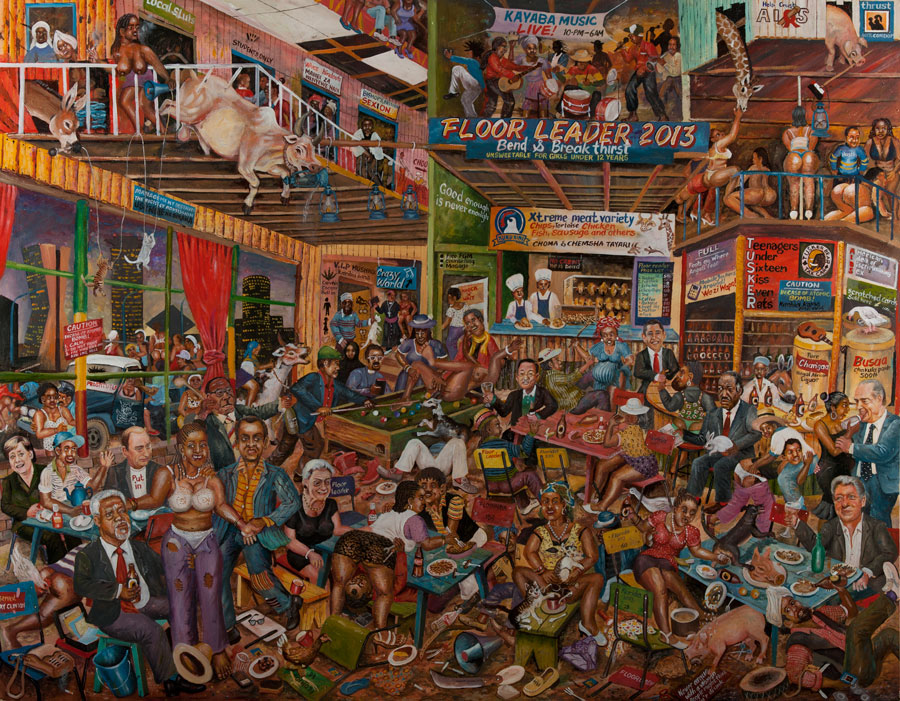

Nchi 1 Barcode, for example, a woodblock by Peterson Kamwathi that auctioned for Ksh375 680 ($4,400), shows the Kenyan flag next to a barcode, questioning the country’s nationhood. Joseph Bertiers, a former painter of homemade signs, makes Bruegel-esque paintings of partying politicians, one of which, The World’s Craziest Bar, sold for Ksh821 800 ($9 600) on Tuesday. Onditi’s paintings show Nairobi’s congested slums superimposed on slave ships, while Soudan’s sculptures are made literally from the ashes of political violence.

Even Wanyu Brush, an old master known for delicate paintings of safari animals and village folk, has moved to tougher subjects and styles in the last few years, with dark lines, jagged brushstrokes, and starker colours seen in his epic Never, Never, Never Again, painted in the wake of Kenya’s 2007/8 post-election violence.

“What you are your seeing right now is Nairobi being activated,” says Soudan.

Still, many Kenyan buyers avoid such cutting edge, confrontational works, preferring decorative pieces instead. Artist Beatrice Wanjiku, for example, who paints distorted human forms and anguished mouths, was not featured in the auction, while a piece by Richard Kimathi, who paints unsettling blue portraits of child soldiers and gaunt animals, was one of the few under the hammer that did not sell on Tuesday.

It will be fascinating to watch where the new attention pushes Nairobi next. Is there momentum to develop more traditional galleries, or will the city continue with self-taught artists and an informal flair? However things progress, what’s clear is that Nairobi has some very high calibre art, and Nairobians are noticing.

Jason Patinkin for Think Africa Press, where this piece was first published.