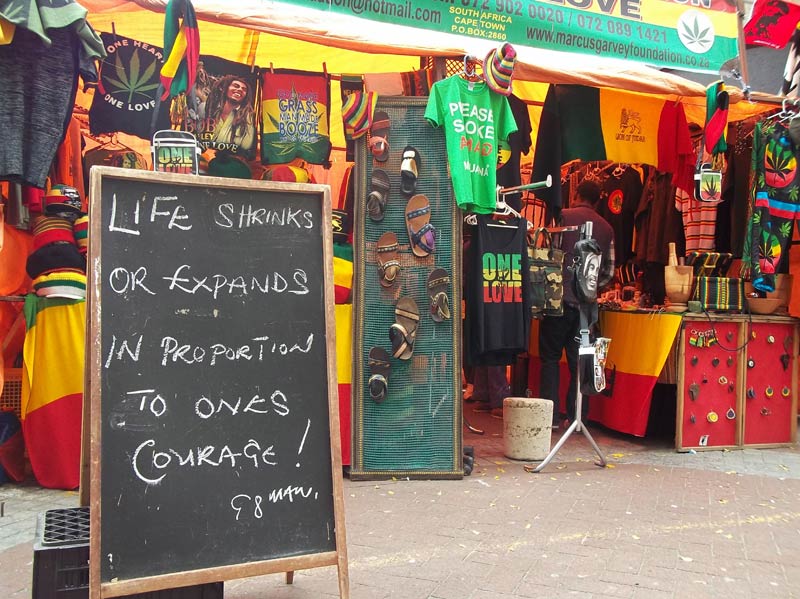

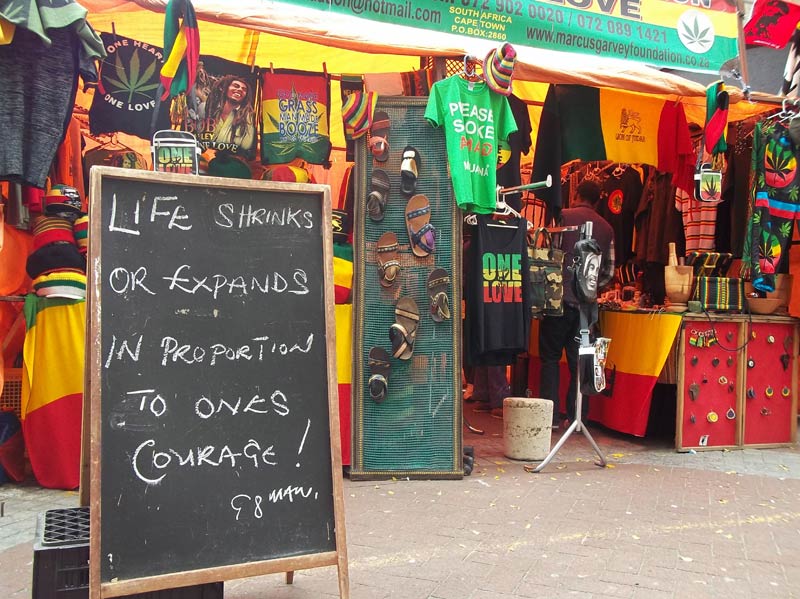

It’s a windy Friday afternoon. I walk through shopping stalls that line a tiny pathway between a fish and chips shop and Woolworths. A kid in a torn T-shirt flashes a 32GB memory stick in my face. I refuse the deal, even before hearing his price. I sink underground in an escalator. At the bottom of it is a man selling newspapers and three women touting various perfumes. A few minutes later, I surface in front of McDonald’s. I dissect the Golden Acre Shopping Centre in half with its walk-through and emerge on the other side that faces Darling Street. Now I’m in front of Jimmy Braye’s Rasta stall. Reggae blares from it; a huge Bob Marley poster flaps in the wind; red, green and yellow clothes are draped everywhere. “Welcome to Jamaica,” it all seems to say, but this is Cape Town.

I start to say sorry for being late but Jimmy quickly stops me. “No need to apologise, my king,” he says. He’s young, loud, big and friendly; Ghanaian but he’s been calling South Africa home since 2003. Before that he spent some time exploring Argentina. “I have been everywhere my king. Singapore, Holland, Togo, Uganda and Australia,” he says proudly.

South Africa beckoned because he saw it as an “economically viable” country. He started out working for Community Peace Project, an NGO based in Observatory, for two years. In 2005, he embraced his passion and opened up his Rasta stall. “I saw a need for it,” he says simply. People come to Jimmy for caps, T-shirts, pants, hoodies, bags, smoking pipes, Rizla and books. He gets his supplies in bulk from Johannesburg.

I ask Jimmy how he finds Cape Town – “It’s beautiful, my king” – and South Africa today. He stares at me for a short while rearranging his thoughts and finding the right words to communicate them. “South Africa is getting there. Its democracy is still young but slowly it is getting there. I hope it does not end up ruined like other African countries. But under the current government, that seems to be happening,” he says. Jimmy tells me he doesn’t follow the news or politics but “South Africa is ready for new leadership. The same thing happening here is happening across the continent. I know this because I’ve been around.”

Apart from the shop, Jimmy runs the Marcus Garvey Foundation out of his home in Vredehoek. He started the project to source funding to build homes for homeless kids. This dream is yet to materialise but he remains hopeful that donors will come on board.

During the two hours I spent with Jimmy, tourists, street kids and passersby dropped in often, some to browse, others to say hi, and some after “a spliff to blaze”. Jimmy smokes weed but doesn’t sell it. “The cops come to search for it but they do not find it because I do not sell any dagga,” he says.

Sales aren’t great but he is happy his stall is still operating after nine years. Making a profit is secondary to doing what he loves, he says. You will find Jimmy here from six to six every day except on Sundays, when he goes to church, and Tuesdays, when he goes to the Deer Park with his fellow Rastas to pray and smoke. He spends his free time working on his project for homeless kids.

Jimmy is one of many informal traders in Cape Town but he’s not only here to make a living; he wants to make a difference. We say goodbye, Rastafarian-style. I pound his left fist with mine and touch his open left palm with my own, and then I step out of Jamaica into Cape Town.

Dudumalingani Mqombothi is a film school graduate who loves reading, writing, taking walks and photography. He plans to write a novel when his thoughts stop scaring him.